Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike. —John Muir

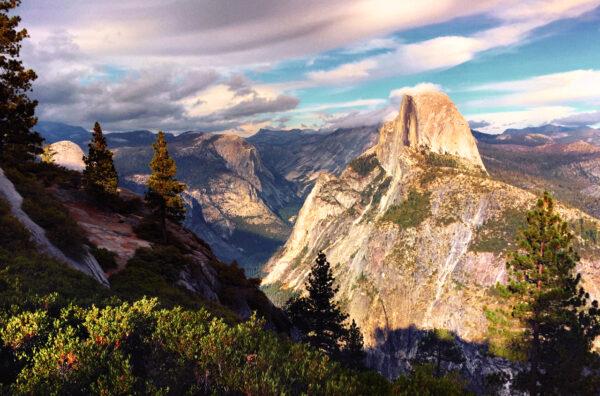

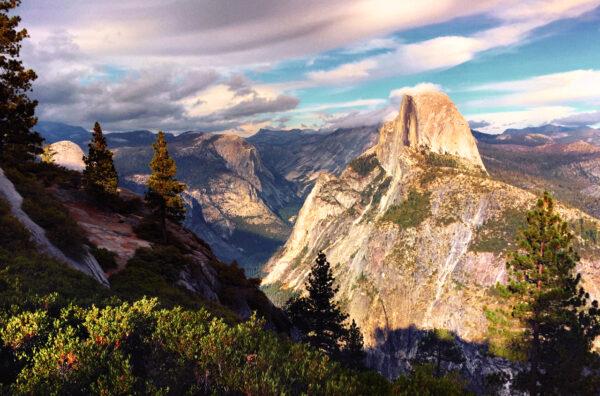

A dramatically beautiful sunset view of Half Dome, as seen from Glacier Point.

Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike. —John Muir