Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael created the epitome of Renaissance art. Most of us know Leonardo’s artistic brilliance through his best-known paintings, the “Mona Lisa” and “The Last Supper,” yet Leonardo’s art is one tiny facet of his legendary genius.

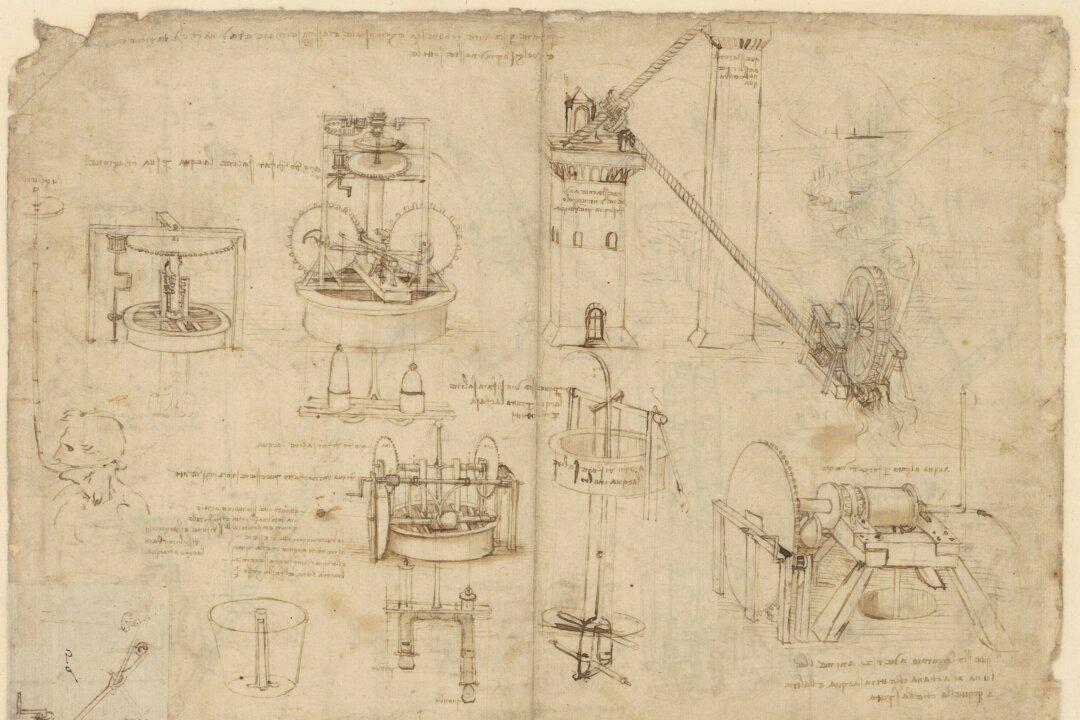

Some may be surprised to learn that he spent many years as an engineer, most notably, around 17 years for the duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza (who also commissioned Leonardo to create “The Last Supper”).