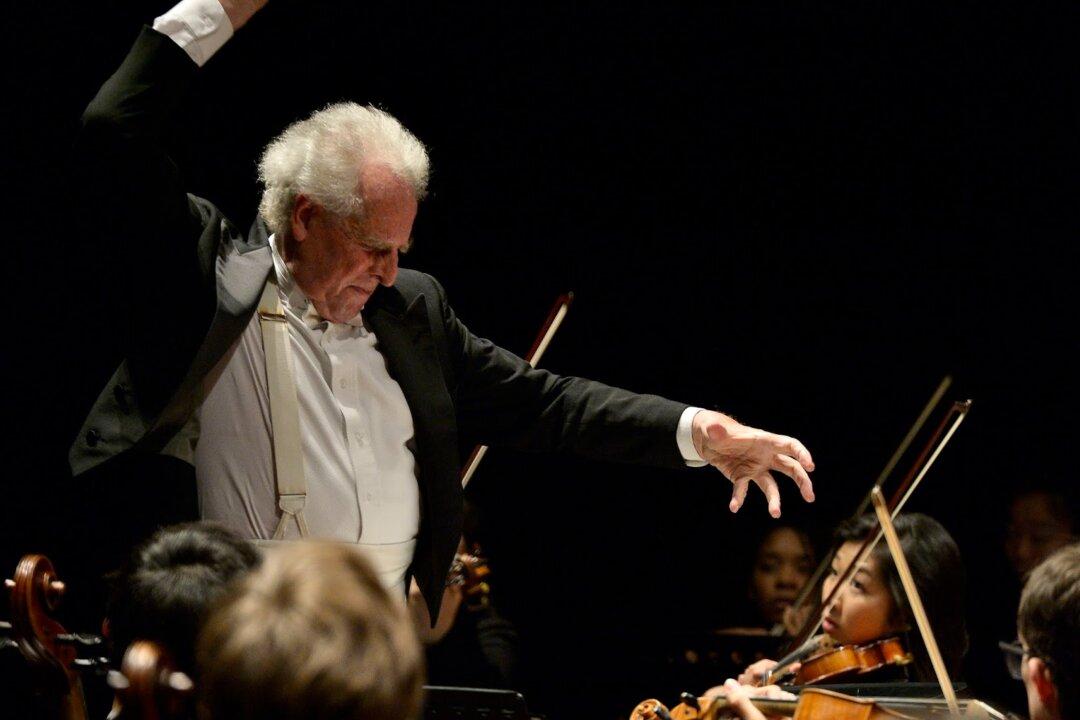

Benjamin Zander’s new recording of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 (“Benjamin Zander Conducts Beethoven Symphony No. 9 ‘Choral’” available on Brattle Media) is the result of a lifetime’s study of Beethoven’s score. But spend any time with Zander and you come to realize both how absorbed by the music he is, and how his study of it has not been intended to perfect his own interpretation but to divine Beethoven’s intentions.

I recently met up with Zander to talk about the new recording and the ideas behind it, particularly with regard to his interpretation of Beethoven’s metronome marks.