When social activists and ideologically driven historians claim that something is evil by virtue of its existence, chances are those who receive that information are missing context. Typically, a lot of context.

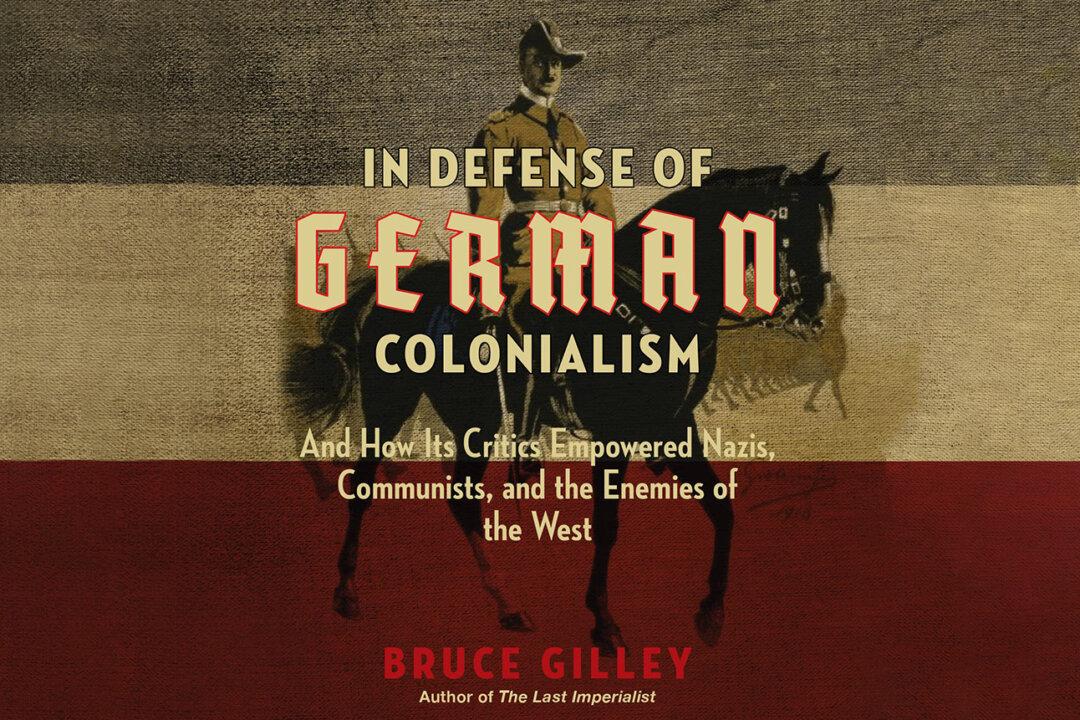

Colonialism is one of those topics regarding which today’s social and political commentators are missing a lot of context, although indeed, they aren’t short on rhetoric. Bruce Gilley, a professor of political science at Portland State University, has written a new book on the subject in an effort to provide more context on colonialism, although he does add his own hyperbolic rhetoric to the mix.