Chinese state media recently released some details of the process of forming the new Central Committee leadership body, from which it can be seen that Chinese leader Xi Jinping did not seek any advice from the senior figures of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the process of preparing the top personnel of the 20th National Congress.

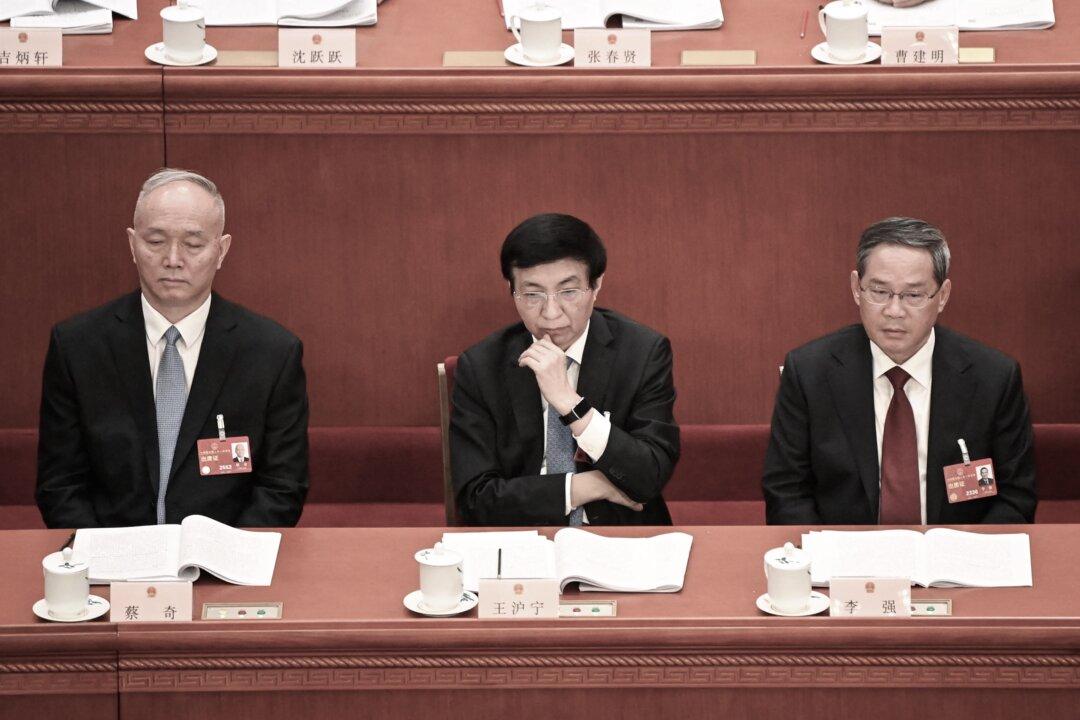

China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency stated in an Oct. 24 article that, starting from April 2022, Xi spoke with “the current members of the Political Bureau of the CCP Central Committee, the secretary of the Central Secretariat, the vice chairman of the state and members of the Central Military Commission—altogether 30 people—and listened fully to their views” when preparing the name list of top leadership.