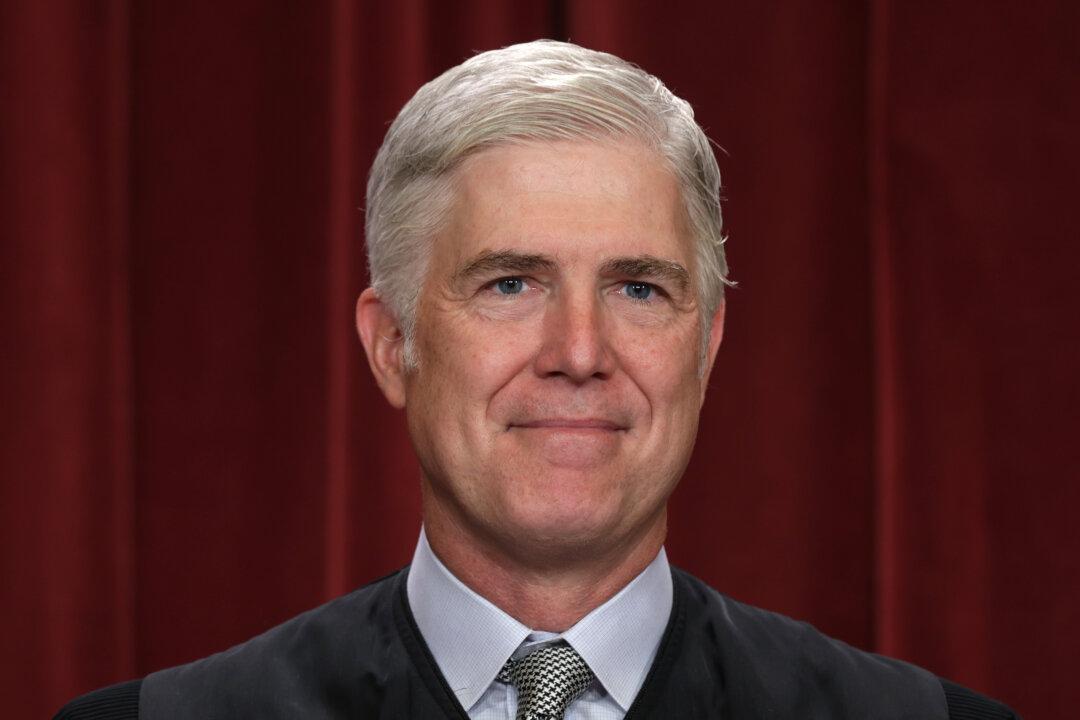

Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch’s new book, which reflects his belief that the United States is over-regulated, will be published this summer.

The work, “Over Ruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law,” is scheduled to be published on Aug. 6 by Harper Collins. Justice Gorsuch is also the author of “A Republic, If You Can Keep It” (2019) and “The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia” (2009).