Commentary

In life’s grand tapestry, woven with threads of triumph and despair, we find ourselves transitioning from one side to the other, traversing the delicate seam between. It’s an idea my friend, Jon Schwartz, eloquently framed as a journey from the left side of despair to the right. I, too, embarked on this passage, navigating through the murkiness of despair, eventually finding myself on its brighter side, the “right” side. As I stand here, I can gaze back across the chasm, tracing the path that once was filled with shadows and is now bathed in a softer light. The echo of that journey has been both a personal transformation and, hopefully, a beacon for others. The resonance of this narrative, however, goes beyond my solitary experience. It’s a testament to the human spirit’s resilience, an affirmation that has sparked a ripple of recognition and optimism among those who have borne witness to it. It’s gratifying to note that my journey, once submerged in despair, now serves as an uplifting testament to the power of perseverance, and most importantly, an example to my children.

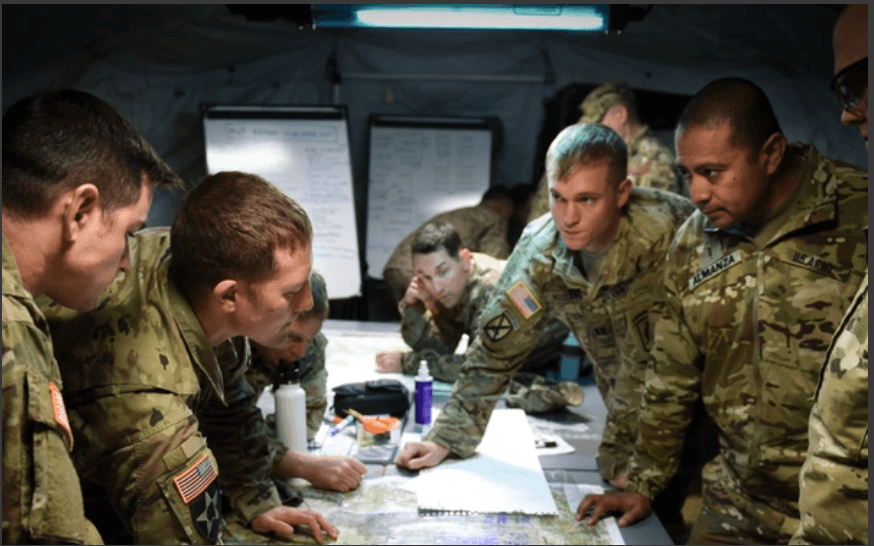

When Dr. Alice Atalanta and I collaborated on our work, “Meditations of an Army Ranger: A Warrior Philosophy for Everyone,” we crafted a distinctive rhythm for each chapter. Each one began with an insightful quote, paving the path for the narrative ahead, and concluded with a poignant poem, which was carefully selected from my personal collection. These verses, penned during my overseas deployment or in the reflective period upon my return, served as thought-provoking finales that echoed the themes of the chapters. One particular chapter about trust concludes with the following verse:

“When I was young, I thought that all men were good. When I went to war, I thought that all men were evil. Now, I realize that all men are just men.”