Ten years after the 2008 financial crisis, the world economy has recovered but the world’s balance sheet has not. Gigantic debt bubbles in stocks, bonds, commodities, and real estate could burst as deflation causes debtors’ income to fall.

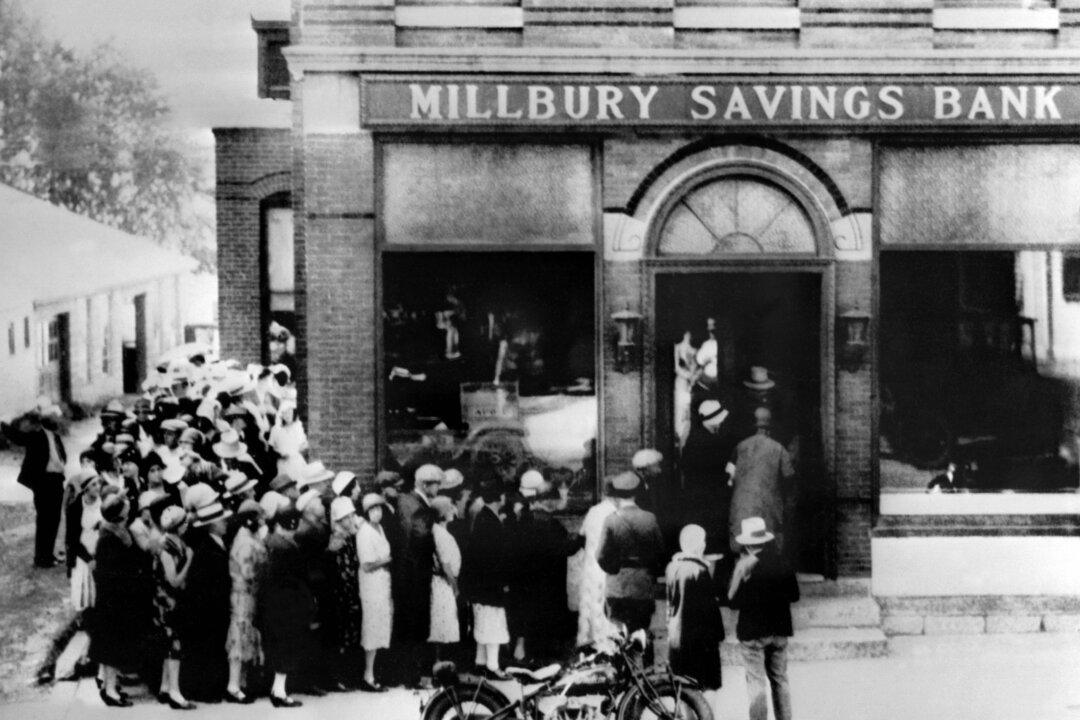

Throughout history, deflation in the context of high debt—around 300 percent of world GDP as of 2017—has always been a recipe for disaster, especially during the series of depressions that rocked the world economy during the last third of the 19th century and during the two major depressions of the 1920s.