Stocks (equity) and bonds (debt) are the two major long-term financial assets typically held by investors. It is common knowledge among investors that the prices of these assets, on average, tend to go in opposite directions.

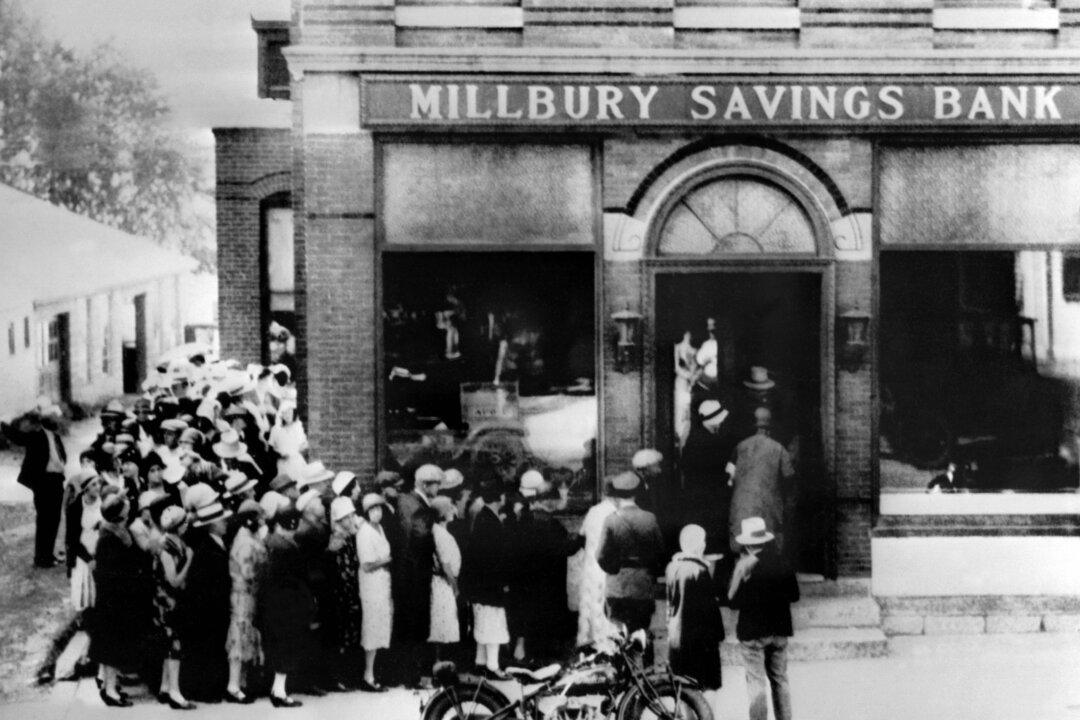

There are two recurring exceptions to this normal trade-off: Boom and bust “culminating points” (as Keynes called them) are periods when stock and bond prices are broadly correlated, rather than moving in opposite directions. So during a general financial crisis, both stocks and bonds may fall in value, wiping out considerable fortunes.