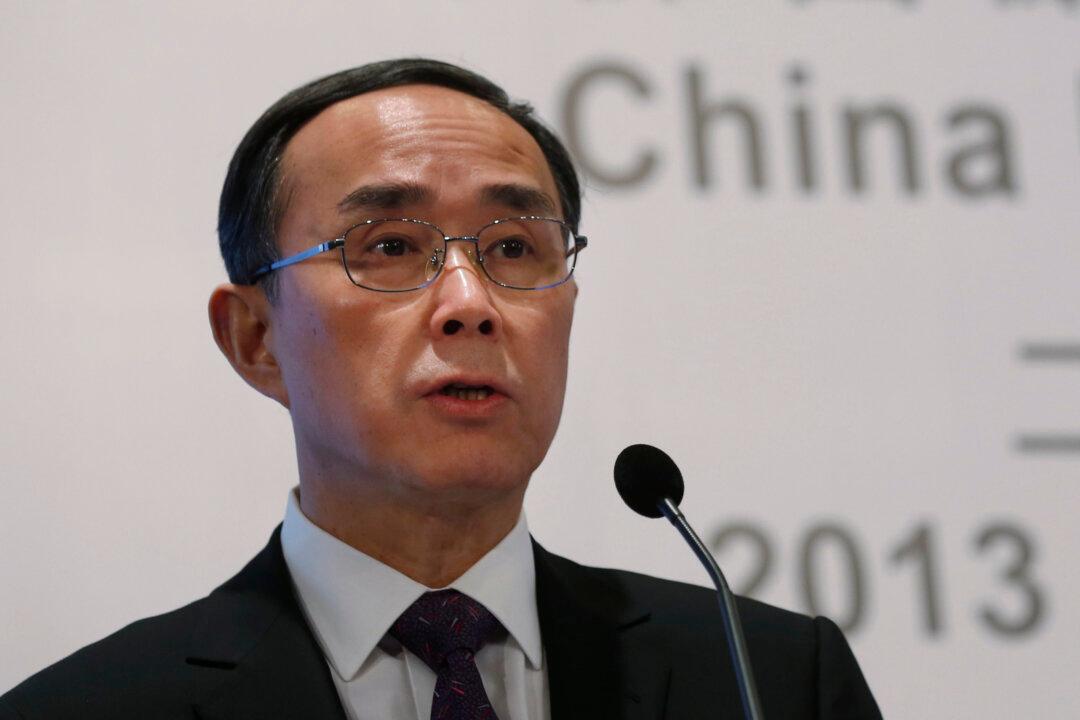

For 11 years, Chang Xiaobing headed two highly profitable Chinese state telecommunication companies. After barely four months as chairman of China Telecom, however, Chang was formally investigated by the Chinese Communist Party’s internal disciplinary agency.

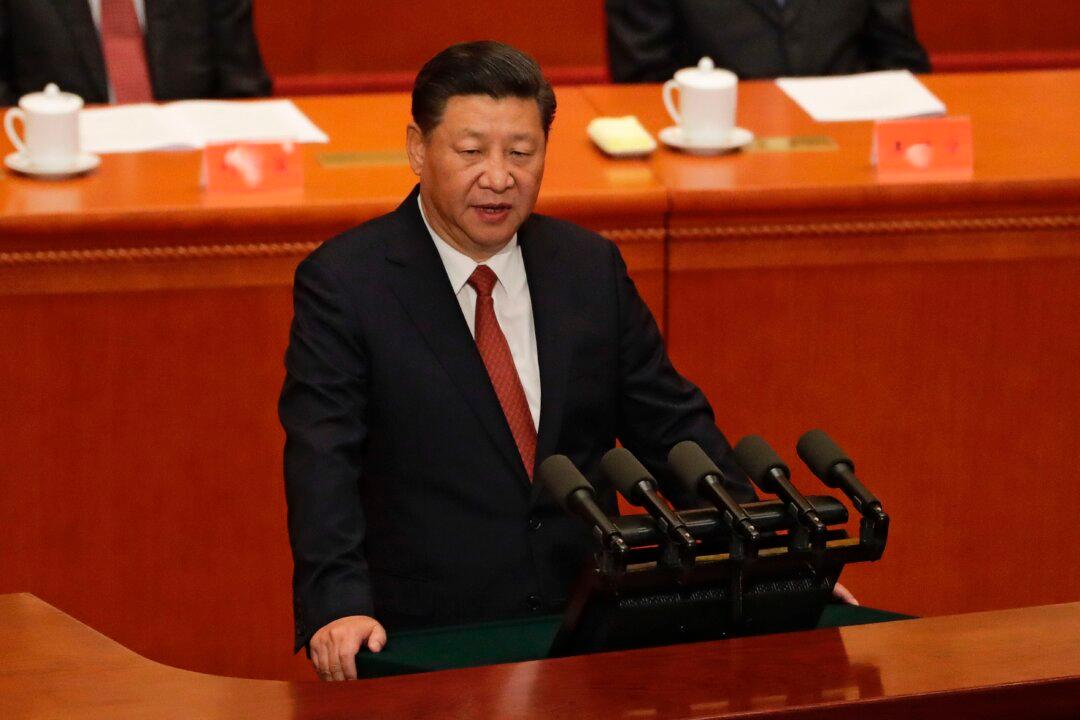

On Dec. 27, the Central Committee of Discipline Inspection (CCDI) announced that Chang, 58, was placed under investigation for grossly breaching Party discipline. The charge usually implies massive bribery and official malfeasance and has been used, it seems, every day since Party leader Xi Jinping began an anti-corruption campaign in early 2013.

China Mobile and China Telecom "formed a parasitic family that hunted and feasted on state assets."

, director of Central Committee of Discipline Inspection 12th inspection team