News Analysis

The Politburo Standing Committee has been the Chinese regime’s top decision-making body in recent history. Thus, Communist Party factions and powerful elders have strived to secure committee seats for their protégés before the National Congress, a crucial political meeting held once every five years during the fall season, where the Party’s top officials are announced.

This fall, however, the committee might no longer be a key factor in elite Chinese politics.

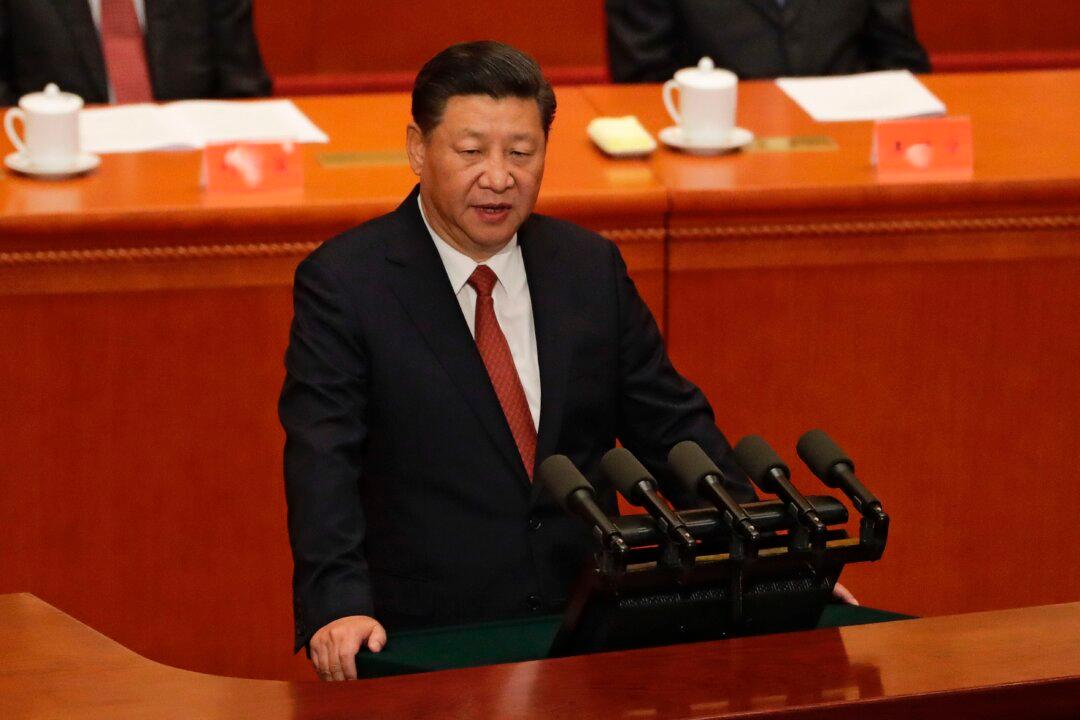

Since the end of July, Chinese leader Xi Jinping has carried out several moves that appear to lend credence to speculation from earlier this year that he intends to break current leadership succession norms and even abolish the committee.

If Xi continues along the current trajectory of power consolidation, the Chinese regime is set to shift at the 19th National Party Congress from rule by a “collective leadership” to a rule of one.