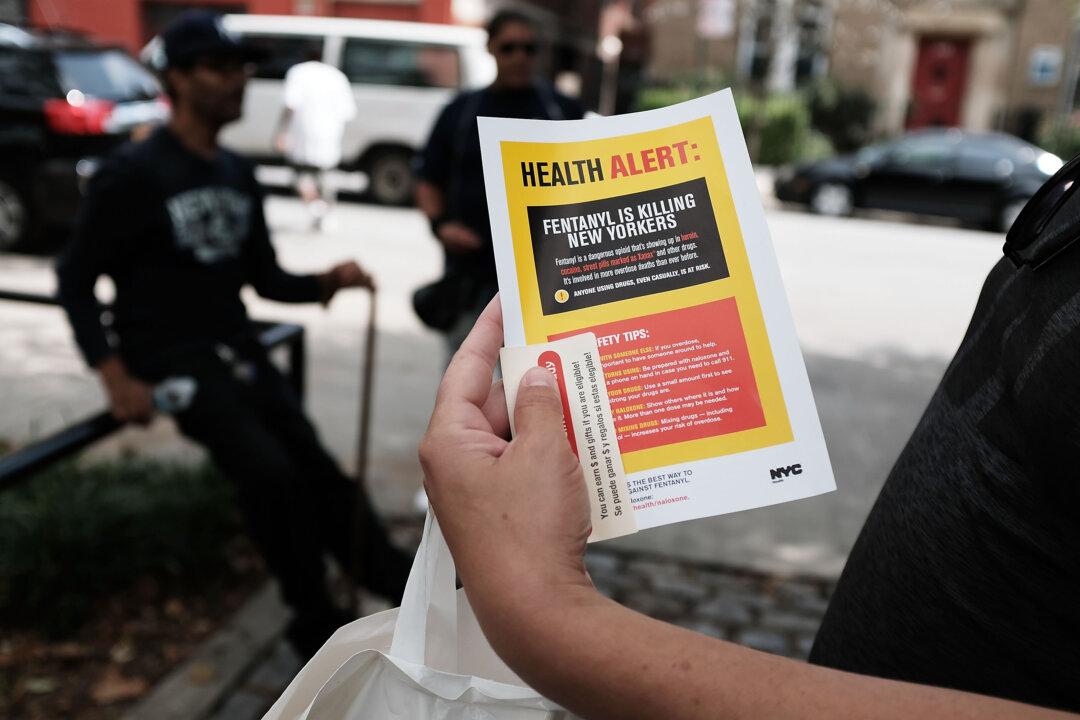

China’s “export-led economic strategy and lack of regulatory oversight” are responsible for most illicit and synthetic fentanyl in the United States, think tank Rand Corporation recently testified to Congress.

The global policy think tank told the U.S. House Homeland Security Committee that the rising opioid epidemic was initially fueled by an oversupply of prescription oxycodone and hydrocodone, but by 2019 morphed into an illicit synthetic opioid crisis causing “approximately two-thirds of all opioid overdose deaths.”