News Analysis

CCP Virus Threatens to Destroy China’s $3.87 Trillion Belt and Road Initiative

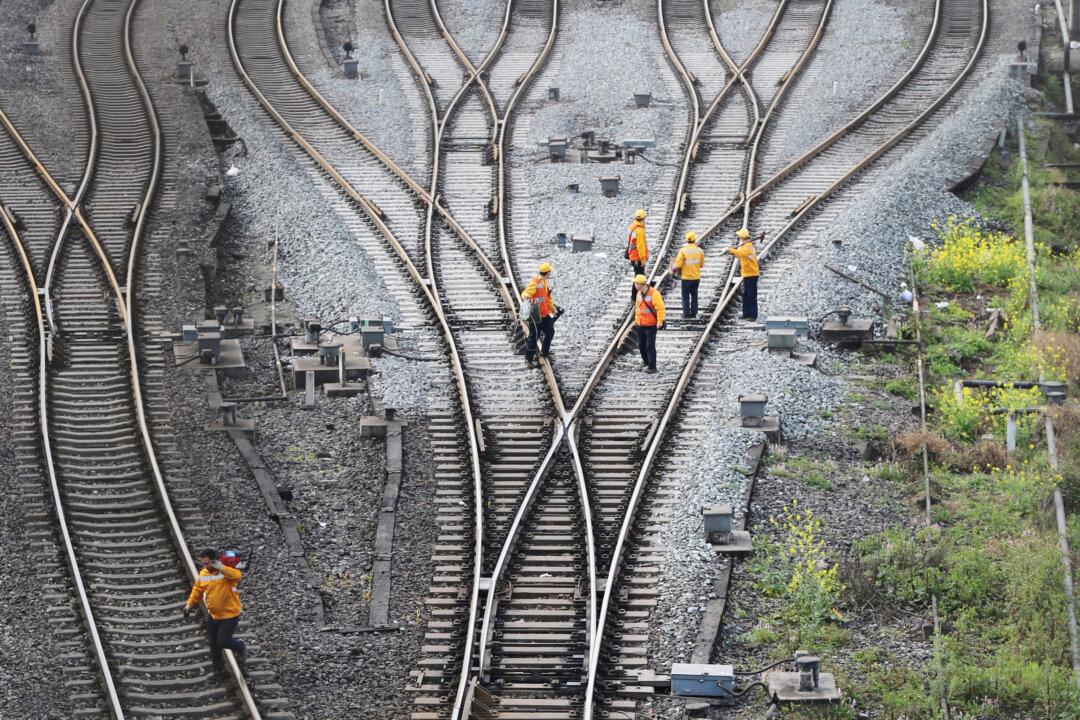

Workers inspect railway tracks, which serve as a part of the Belt and Road Initiative freight rail route linking Chongqing to Duisburg, at the Dazhou railway station in Sichuan Province, China, on March 14, 2019. Reuters

|Updated: