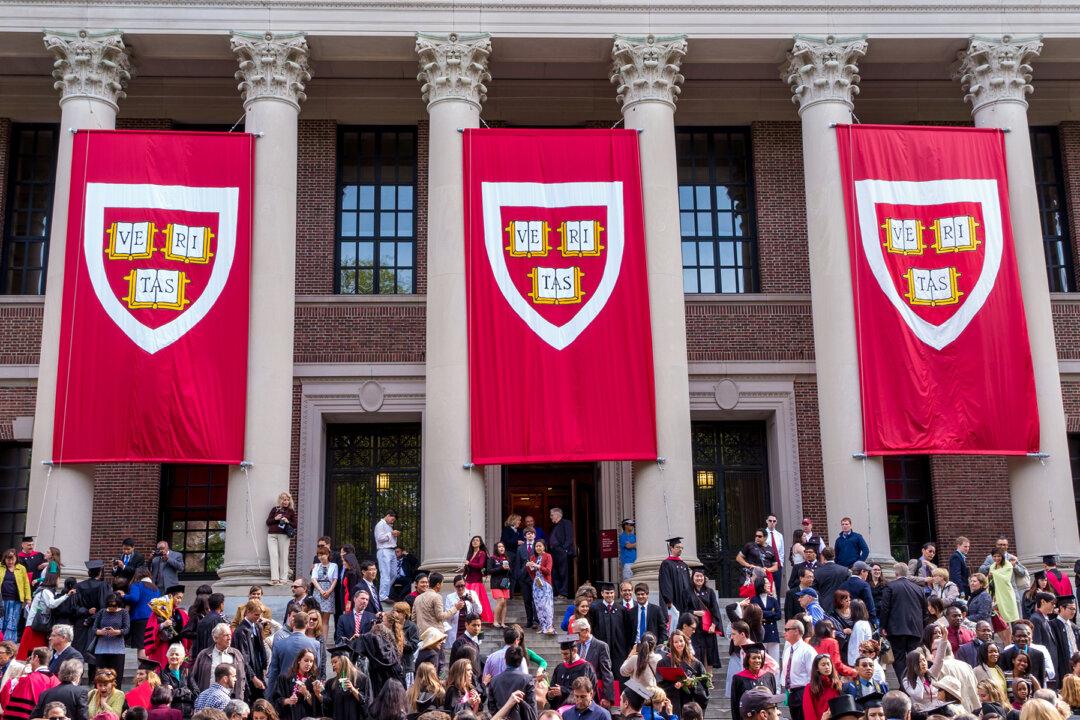

A large cross-section of corporate America filed briefs with the Supreme Court on Aug. 1 urging the court to allow colleges to continue using race as a factor in student admissions.

The court is poised to hear challenges to these racially discriminatory policies in its new term that begins in October. The challengers say so-called affirmative action not only hurts white applicants, but works out to be an “anti-Asian penalty” as well. Asian American applicants generally have higher academic scores and higher extracurricular scores, they say.