Commentary

Carla Gleason/Department of Defense

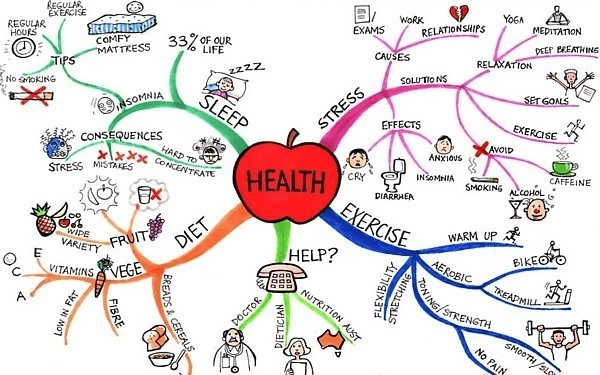

Jenna Warnock comes from an Army family and is a dietetics student currently attending Appalachian State University. Her interest areas include hormonal health, functional medicine, and public health with the intent of becoming a registered dietitian for the veteran population. Jenna is also an RD2BE [Registered Dietician 2 BE] intern and serves as an RD2BE social media and marketing intern, a student host of the RD2BE Podcast, and a content developer.

Author’s Selected Articles