DARIÉN GAP, Panama—The grind of heavy machinery breaks the silence of the Darién jungle, where the Pan-American Highway ends at Yaviza, Panama.

Construction workers have cleared towering trees to make way for a steel and concrete bridge mighty enough to withstand flooding from the Chucunaque River.

An onsite worker for the construction company Cusa told The Epoch Times that the construction project will cut four miles into the Darién jungle at a cost of $42 million and includes a second bridge crossing the Tuira River.

That would leave some 55 miles to finish the Pan-American Highway, also known as Highway 1, through the mountainous rainforest to connect it to Turbo, Colombia.

If it’s ever completed, the Pan-American Highway will stretch about 18,000 miles from Alaska to Argentina, opening up a land corridor the length of the Americas.

It has gone unfinished for decades because of American and Panamanian concerns over the environment, crime, and disease—and more recently, mass migration. The dangerous, rugged terrain acts as a natural barrier to travel from South to Central America.

The bridge and road expansion will end near the town of Bocas de Cupé in the Darién Gap. However, bridging the rivers has been considered one of the major obstacles blocking the completion of the highway.

The new project has worried some who fear that completing the road into the Darién Gap will be a win for China and a loss for the United States.

Michael Yon, a former war correspondent, has been covering mass migration through Panama for several years and has used social media to bring attention to the bridge’s construction and its implications.

China would benefit through an alternate trade route around the Panama Canal, which is essential to global trade. But for the United States, it could open the floodgates to migrants from South America, he told The Epoch Times.

U.S. leaders have grown increasingly wary of the military implications of Chinese infrastructure projects being built in America’s backyard as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), particularly around the Panama Canal.

In 2017, Panama signed on to China’s ambitious BRI project, dubbed a modern Silk Road, after publicly recognizing Taiwan as part of China, much to the surprise and concern of the United States.

She and other commanders in recent years have been sounding the alarm about China’s incursion into the Western Hemisphere.

Closing the Gap

Last year alone, a record 500,000 migrants traveled through the Darién Gap on their way to the U.S. southern border, documents show.

Mike Howell, director of The Heritage Foundation’s Oversight Project, believes that China’s economic development in the region threatens U.S. influence and security.

“If China displaces the U.S. in the Western hemisphere as the dominant economic power, then we lose our leverage,” Mr. Howell, formerly an attorney with the Department of Homeland Security, told The Epoch Times.

China is encircling the United States with infrastructure in Latin America and the Caribbean, he said.

“It’s like a boa constrictor that’s tightening and tightening around the United States,” Mr. Howell said.

In the 2019 book “China’s Belt and Road and Panama: A Strategic and Prospective Scenario Between the Americas and China,” author Eddie Tapiero touted the rise of China’s BRI in utopian terms.

Mr. Tapiero, a Panamanian professor and international economist who wrote his book after a BRI meeting in China, called the initiative a catalyst for “global public good,” envisioning a world where “borders no longer exist, nor do countries.”

The book includes a BRI scenario, with a map titled “Globalized Belt and Road” showing Panama and its canal connected to Colombia by rail through the Darién Gap.

On the Colombian side of the Darién Gap, Chinese companies are working to build highways and ports.

Roadwork near the Pan-American Highway in Turbo is part of the “Autopistas al Mar 2” highway project.

The project will connect Colombia’s second-largest city of Medellín to ports in Urabá, including Turbo, where the Pan-American Highway ends.

The project was delayed until late 2019, when the Chinese-led consortium obtained the necessary loans from the China Development Bank.

Mr. Tapiero sees Panama, bookended by Colombia and Costa Rica, as a central hub in Latin America for the BRI. He suggested that the United States could “reduce geopolitical uncertainty” if it, too, joins the BRI.

His globalized BRI map also shows rail routes slicing through the United States to significant markets on America’s east and west coasts.

Infrastructure “connectivity” through air, land, and sea is a central theme of the book, which is playing out in Panama.

The bridges into the Darién are part of a contract for the rehabilitation, improvement, and maintenance of the East Pan-American Highway.

The investment for the project stands at more than $262 million as part of Panama’s Performance Standards Maintenance Program, which aims to promote agricultural, commercial, and tourist development.

Global Choke Points

A highway through the Darién Gap stands to diminish the importance of the Panama Canal, which the United States still protects under a neutrality treaty.The canal was returned to Panama in 1999 under a treaty brokered in the 1970s with President Jimmy Carter.

The Darién Gap by land is similar to the Panama Canal by sea as a choke point, which holds military and economic value.

China’s attempt to minimize or control the canal’s strategic importance to the United States could be significant should a conflict break out over Taiwan in terms of China’s ability to shut down sea lanes, according to Andrés Martínez-Fernández, The Heritage Foundation’s senior policy analyst for Latin America.

“That’s a very concerning issue in particular,” he told The Epoch Times.

Mr. Martínez-Fernández noted that Chinese companies have been busy building infrastructure on either end of the U.S.-built Panama Canal.

The canal has become a point of tension between China and the United States, which has retained the right to enforce operational neutrality on the Panama Canal.

The Panama Canal Authority controls the administration and maintenance of the waterway’s resources and security, independent of the Panamanian government.

Chinese businesses invested heavily in the canal zone under former Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela, but projects have been dropped or limited under the current administration of President Laurentino Cortizo.

Two of Panama’s five principal ports are controlled by China through Hong Kong-based Hutchison, with one at Balboa on the Pacific side and another at Cristobal on the Atlantic side, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank.

Work conducted by Chinese companies on the enormous Amador Pacific Coast cruise terminal is nearing completion.

These projects followed China-based Landbridge striking a $900 million deal in 2016 to control Margarita Island, Panama’s largest port on the Atlantic side, to build a deepwater port.

The state-owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) is building the port for mega-ships. CCCC was involved in constructing China’s man-made islands in the disputed South China Sea and is part of CHEC.

In 2018, a Chinese consortium headed by CHEC and CCCC was awarded a $1.4 billion contract for the canal’s fourth bridge.

In 2019, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned Mr. Varela about state-owned Chinese businesses that engaged in “predatory economic activity.”

Criticism has grown that China’s BRI is a debt trap plagued by waste and questionable loan repayment tactics. Detractors claim that it allows China to control or own projects when governments cannot repay their loans.

China’s growing influence in Latin America should not be underestimated, according to Mr. Martínez-Fernández.

“So what happens in the Western Hemisphere, I would argue, has more direct impacts on the United States than in most parts of the world because of those direct ties on the avenues of migration, economy, and security,” he said.

Of the 31 nations in Central and South America, Panama was the first of 22 to formally sign onto China’s BRI program, with Honduras being the latest.

Belt and Road

Miles Yu is director of the China Center at Hudson Institute and a former China policy adviser to Mr. Pompeo.“The Panama Canal—China has always wanted to control that,” he told The Epoch Times.

That’s because canals have both military and commercial significance, according to Mr. Yu, a professor of East Asia and military and naval history at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

Beijing is also intent on controlling the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca between Indonesia and Singapore, he said.

Controlling sea routes has always been an obsession for China because of their dual value, according to Mr. Yu.

In the past decade, a Chinese businessman explored the idea of cutting a canal through Nicaragua to bypass the one in Panama, an idea that the United States abandoned in the early 1900s.

The United States favored digging the canal in Panama because the route was shorter and avoided a string of active volcanoes hindering the Nicaraguan route.

Deepwater ports are also an integral part of the BRI.

Currently, China is backing the construction of a massive shipping port in Peru that military experts worry could serve as a base for warships.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping is scheduled to visit Peru in the latter half of 2024 to mark the completion of a $3.6 billion port near Chancay, which is financed, built, and owned by China or Chinese-backed companies.

Right above the U.S.–Canadian border, China and former Vancouver Premier Christy Clark signed a memorandum to build the Vancouver Logistics Park, originally dubbed the “World Commodity Trade Center.”

Phase one of the $190 million, 470,000-square-foot complex, billed as a BRI project, has been completed.

Canadian subsidiaries North America Commerce Valley Development Ltd. and Shing Kee Godown Holdings Ltd. are in partnership with local development firm Pollyco Group, according to the trade publication.

In Mexico, Chinese companies operate mines and provide 80 percent of Mexico’s telecommunications equipment. China’s CCCC is also building part of the Maya Train rail system across five states in Mexico.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico’s left-of-center president, has pushed the rail project, which fits with the United Nations’ 2030 goals, as a way of promoting social justice for impoverished areas.

In the Caribbean, China built a colossal embassy in the Bahamas, where the United States last had a permanent ambassador in 2011. Chinese companies have poured billions into ports and roads on the islands just 50 miles from the U.S. coast.

Trade and investments in sea, space, telecommunications, minerals, and energy between China and Latin American countries will match the United States by 2035, according to estimates from the U.S. State Department.

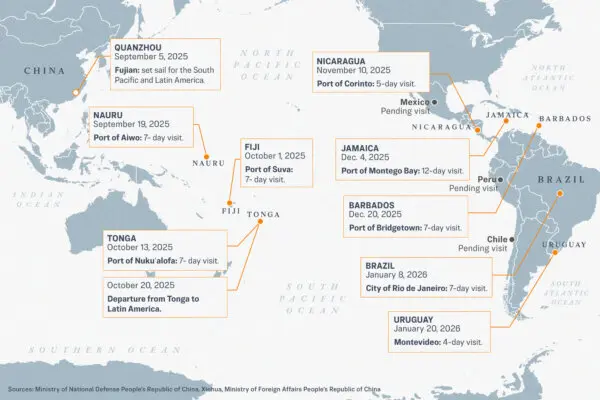

More troubling, China’s warships now make port visits to Venezuela, Cuba, Peru, and Chile, which are expected to mature into base agreements in 10 years.

Experts say the United States needs to catch up to the challenge of Chinese influence.

At the G20 summit in 2023, the United States and its partners revealed an economic corridor linking India, the Middle East, and Europe.

Heads of state from Canada, Barbados, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay, Mexico, and Panama attended the White House event.

The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and the Inter-American Development Bank will establish an innovative joint investment platform to channel billions of dollars in financing for sustainable infrastructure and critical economic sectors in the Americas.

The investments of the Americas Partnership Platform will help build modern ports, clean energy grids, and digital infrastructure, according to the White House.

Mr. Martínez-Fernández said that while the program is a start, it lacks trade commitments and solid investments from the United States.

“That’s what regional leaders and partners are looking for,” he said.

“Certainly, for the level of risk that we’re seeing, the level of attention is not sufficient.”