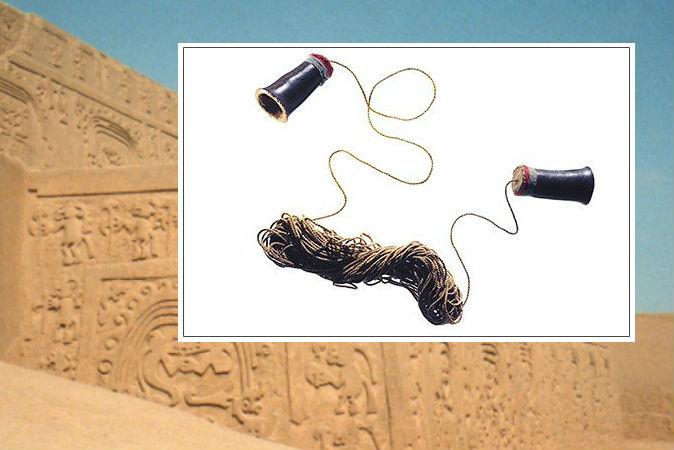

The Peruvian telephone thought to have been made 1,200 to 1,400 years ago, a marvel of ancient invention, surprises almost all who hear about it. Found in the ruins of Chan Chan, Peru, the delicate communication artifact is known as the earliest example of telephone technology in the Western hemisphere.

This seemingly out-of-place-artifact is evidence of the impressive innovation of the coastal Chimú people in the Río Moche Valley of northern Peru.

Ramiro Matos, curator of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) told Smithsonian: “This is unique. Only one was ever discovered. It comes from the consciousness of an indigenous society with no written language.”

A man dressed as a Chimu elite or priest among the ruins of Chan Chan, Peru. Johnathan Hood/Flickr/CC BY-ND