Population decline is “the most serious crisis humanity is facing” and could result in shrinking communities, intergenerational strife, and societal collapse, a data scientist and demographer has warned.

The data scientist, whose documentary “Birthgap” delves into the reasons behind falling global populations, said that while humanity is facing a number of crises, population decline is the most serious because no known civilisation has recovered from it.

“In fact, there’s evidence that this is exactly how civilisations end,” Mr. Shaw said, detailing that the Roman Empire in its latter stages had put in place policies to try and increase birthrates including taxes on the childless.

“There are Roman experts who put demography as one of the reasons that the Roman Empire—well, it didn’t fall overnight—it basically faded away. And that’s exactly what’s happening to us, now. We’re fading away. This is what it feels like to fade away,” he said.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics put the total fertility rate (TFR) in England and Wales at 1.49 children per woman in 2022, a decrease from 1.55 in 2021. The TFR has been decreasing since 2010.

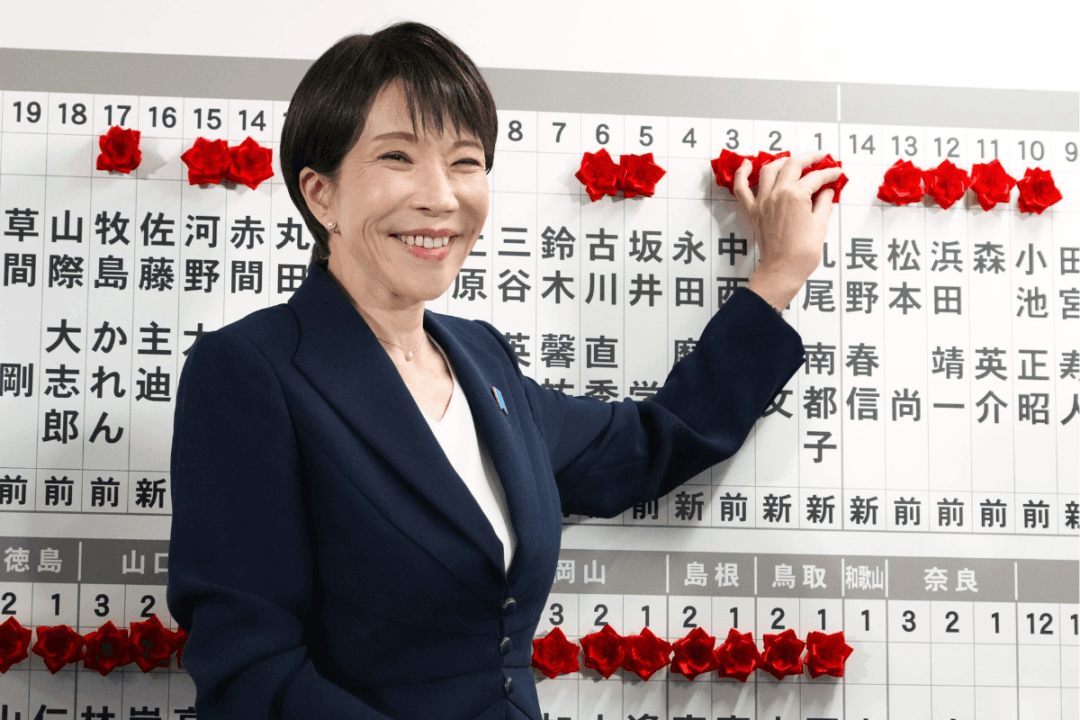

Mr. Shaw pointed to other developed nations well-known for declining birthrates such as Italy and Japan, but added that since 1980, the average woman in sub-Saharan Africa has been having one fewer child every 15 years.

Rise in Childlessness

The statistician looked into declining birth figures to try to find a reason behind it. He discovered that the TFR was misunderstood because demographers were applying it to the concept of the “average woman,” which led to the perception that the average woman was having fewer children.“I think we’ve known, culturally, for some decades, that there’s no such thing as an average woman,” he said.

“What we find is, if we look at average family size, across all of those nations, since around 1970, there has been no change.

“What has changed is a rocketing amount of childlessness, most of which I believe is unplanned. It’s delayed parenthood leading to a large number of people in these countries becoming childless for life,” Mr. Shaw said, explaining that the UK is looking at 30 percent of women being on a path of childlessness.

Even in terms of large families, in 1970, 6 percent of Japanese mothers were having four or more children, Mr. Shaw said. “Today, it’s exactly the same,” he added.

Mothers in the UK are also having the same number of children—2.3—while the United States has seen a slight increase in half a decade from 2.4 to 2.6.

“So it seems to be that motherhood is incredibly robust, once someone becomes a mother,” he said.

The demographer said that despite substantive social and economic changes that have affected women in the past 50 years—such as women’s education and employment—“the average mother is having the same number of children as 50 years ago.”

‘Baby Shocks’

One factor Mr. Shaw saw as a reason for declining birthrates was what he termed “baby shocks”: events in the global economy—such as oil or currency crises—that cause couples to delay having children.One major baby shock occurred around the time of the 1973 oil crisis, which affected countries including the UK, Japan, and Italy, and saw birthrates falling that following year, the demographer said. In the United States, there were two baby shocks: the 1971 “Nixon Shock” when the country came off the Gold Standard and the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

There is no recovery from these shocks, Mr. Shaw said, and these are what contribute to lifelong childlessness. He said that prior to 1973, childlessness was “negligible” at less than 5 percent in the UK. Within three to four years, that proportion had increased to over 20 percent and the nation is now heading towards 30 percent lifelong childlessness.

However, these baby shocks have no impact on women who are already mothers, Mr. Shaw said, reinforcing his concept that motherhood is resilient.

Anti-Natalist Movement

Mr. Shaw criticised the persistence of Malthusian demographic theories, including those expounded in the 1968 book “The Population Bomb” by Paul R. Ehrlich, which claim that global populations will become so great that we will run out of resources.“That viewpoint is still ingrained in people’s minds,” he said.

Anti-natalists and the environmental movement are also hampering discussion on how to resolve the population crisis, with the former putting focus on women having careers over motherhood.

“Anti-natalists have had it their own way for decades, preaching about this nonsense in terms of how low birth rates can improve the environment,” he said.

He added that these voices that dissuade women from motherhood “have been really cruel to women who want to be mothers, which is, frankly, most women.”

Population decline could also cause increased tensions between generations, he said, noting that already, younger voices are blaming the “boomer generation” who as they age are using more resources, such as health services, with ever-smaller pools of younger people to support them.

However, the demographer noted that younger generations are unaware that they, too, will age and need care from a younger population that will be even smaller than their own.

The Hungarian Response

The demographer mentioned Hungary as one country making a concerted effort to reverse its population decline, including introducing family-friendly government policies like tax breaks and loans to encourage parents to have children.Mr. Shaw said that while Hungary was some way off from returning to replacement level, it had increased its birthrate from 1.2 per woman to 1.5 and has seen a notable increase in marriage rates in younger people.

“Back in 2010, a teenage girl in Hungary, based on societal patterns, would have had a 42 percent likelihood of remaining childless for life. That fell very quickly down to 28 percent. We haven’t see that anywhere else,” he said.

“Are we hearing enough about this? No. Every country should be talking about this in their parliaments, looking at Hungary and saying, ‘We’ll try that,'” Mr. Shaw remarked.

“Let’s not wait another 10 years to find out how Hungary progresses, because you'd lose another 10 years of birthrates going down and down and down,” he warned.

“It’s frightening because it’s a problem that gets worse, day by day, year by year, but you don’t feel it,” he said. “You don’t read it in the news. And that’s one of the most unfortunate things that just creeps up over decades.”