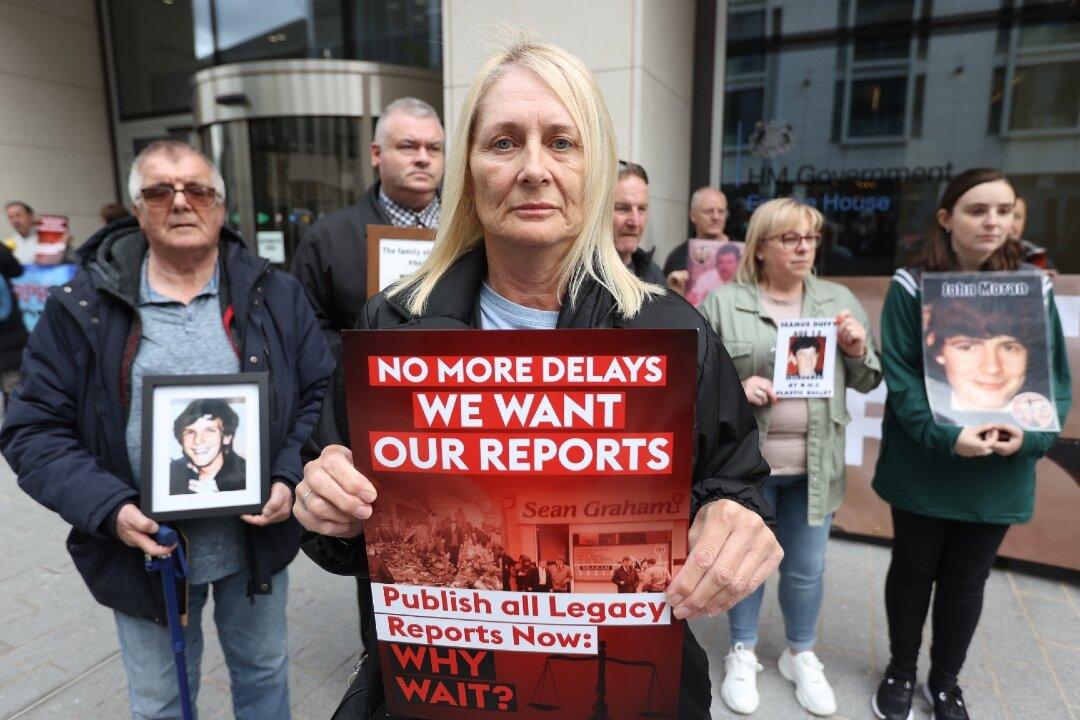

MPs have overturned attempts to remove a conditional immunity provision from contentious legislation aimed at halting post-conflict prosecutions in Northern Ireland.

The House of Lords had voted to tear up an element of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill, which offers those accused of Troubles-related crimes immunity from being prosecuted if they cooperate with a new truth-recovery body.