OTTAWA—The Liberal government waited until the House of Commons was about to adjourn for three months to introduce a bill aimed at protecting Canadians from online hate speech.

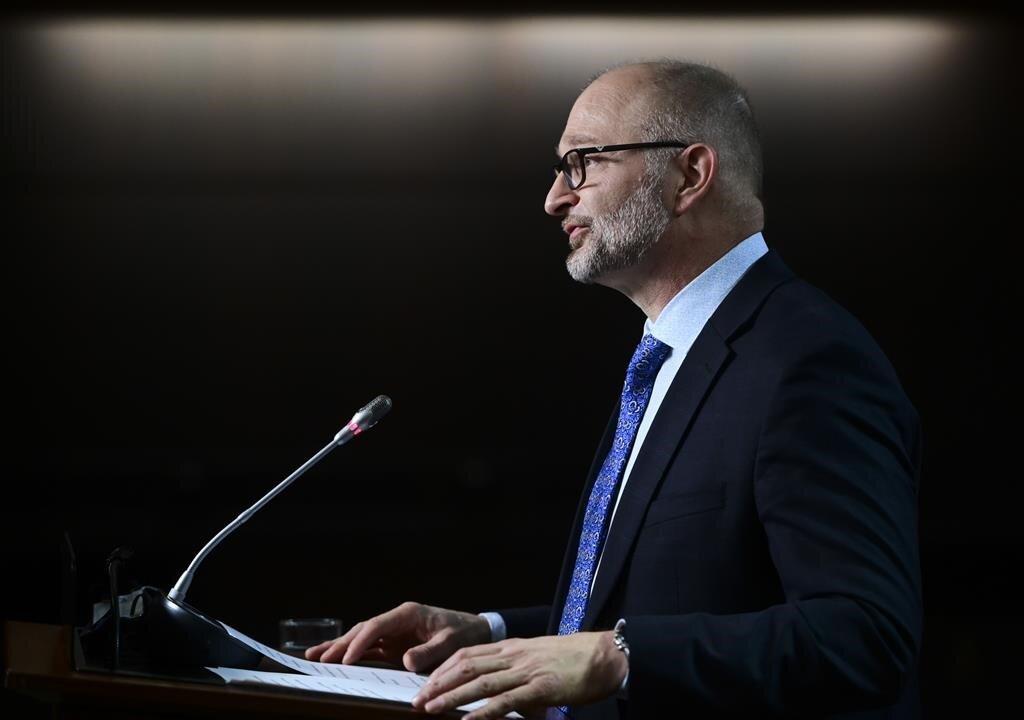

David Lametti, Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, delivers a statement on Bill C-7 during a media availability on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on March 11, 2021. The Canadian Press/Sean Kilpatrick

|Updated: