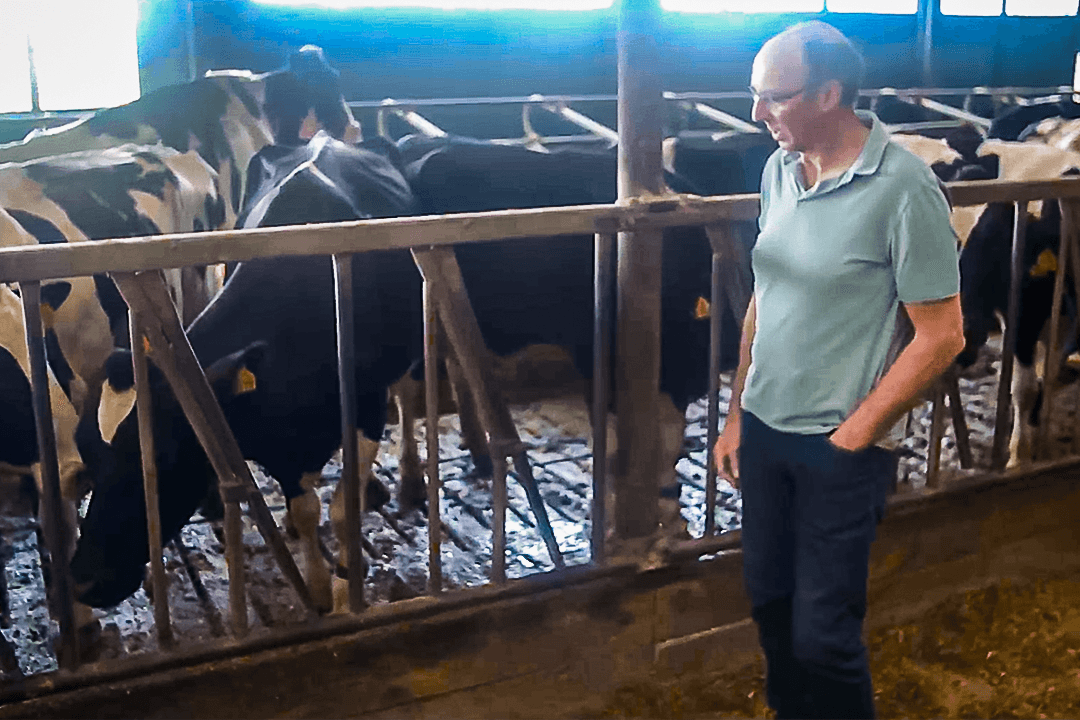

In the Netherlands, dairy farmer Martin Neppelenbroek is near the end of the line.

New environmental regulations will require him to slash his livestock numbers by 95 percent. He thinks he will have to sell his family farm.

In the Netherlands, dairy farmer Martin Neppelenbroek is near the end of the line.

New environmental regulations will require him to slash his livestock numbers by 95 percent. He thinks he will have to sell his family farm.