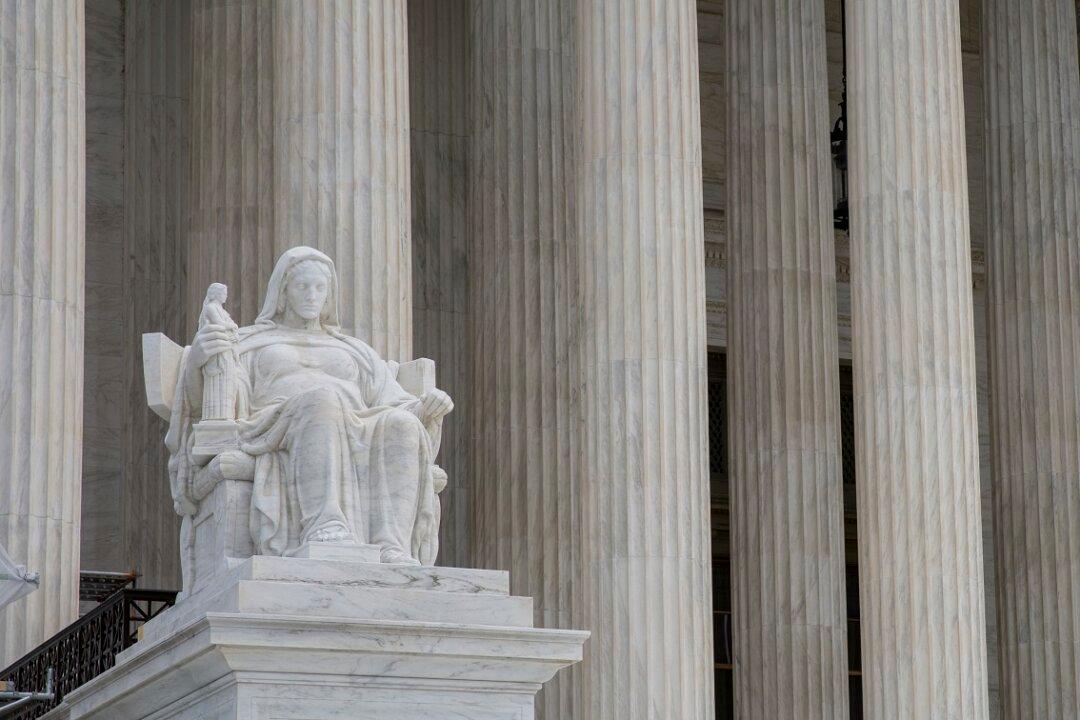

WASHINGTON—A disputed trademark that is pronounced the same way as a vulgar swear word constitutes speech that should be protected by the government on First Amendment grounds, a lawyer for a clothing designer told the Supreme Court.

The hour-long oral arguments on April 15 took on a surreal air as justices performed a kind of linguistic ballet, carefully avoiding saying the trademark aloud.