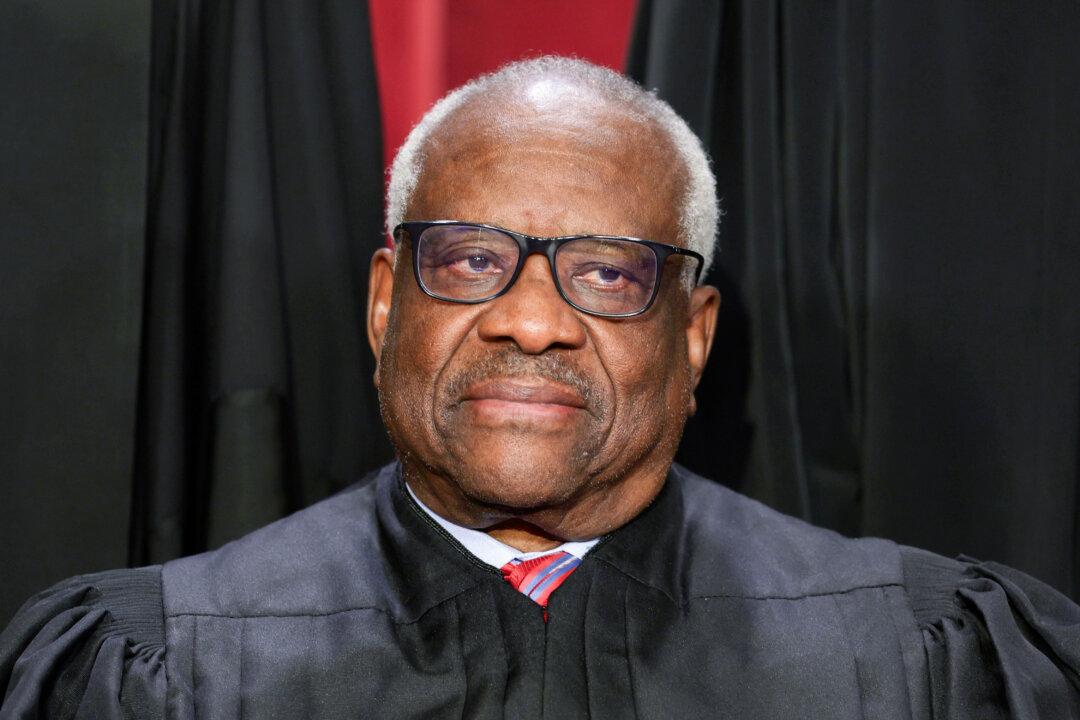

Justice Clarence Thomas on June 21 dissented in a major gun case, saying that a law that prohibits certain people from owning firearms violates the U.S. Constitution’s Second Amendment. The eight other justices sided with the government.

The law, 18 U. S. C. §922(g)(8), bars people who are subject to restraining orders against a partner, ex-partner, or the child of either from owning or possessing guns.