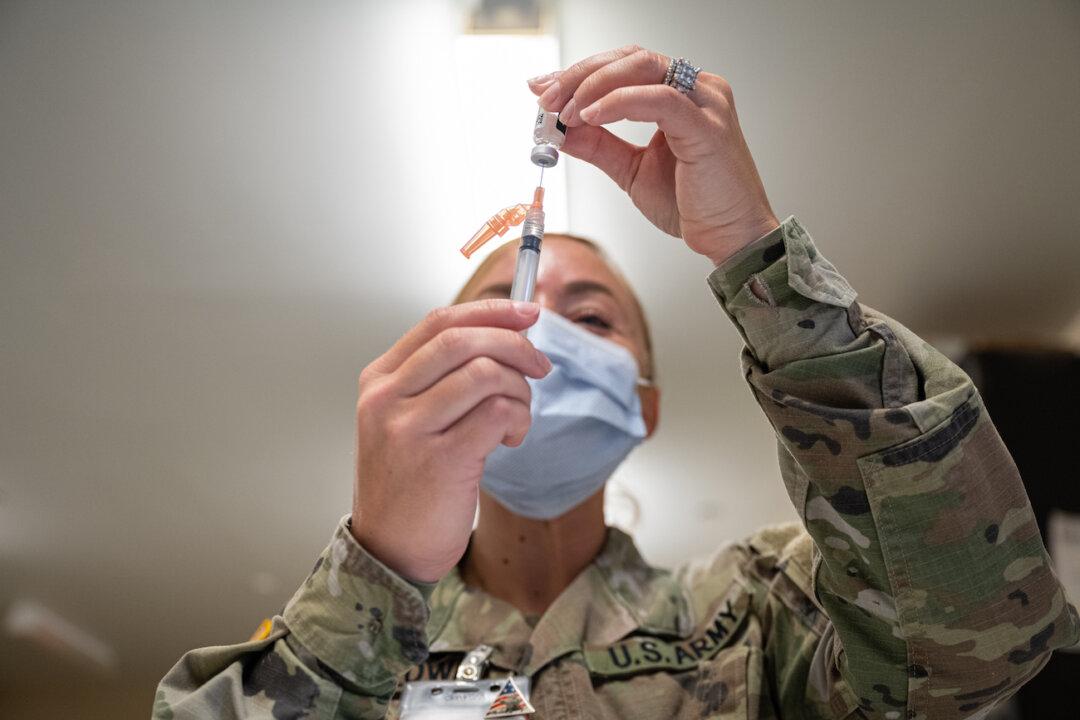

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which awaits President Joe Biden’s signature, ends the requirement for military members to be vaccinated for COVID-19.

But it doesn’t say what happens to the people who have refused the COVID shot and were either kicked out of the military or who are in the middle of the separation process.