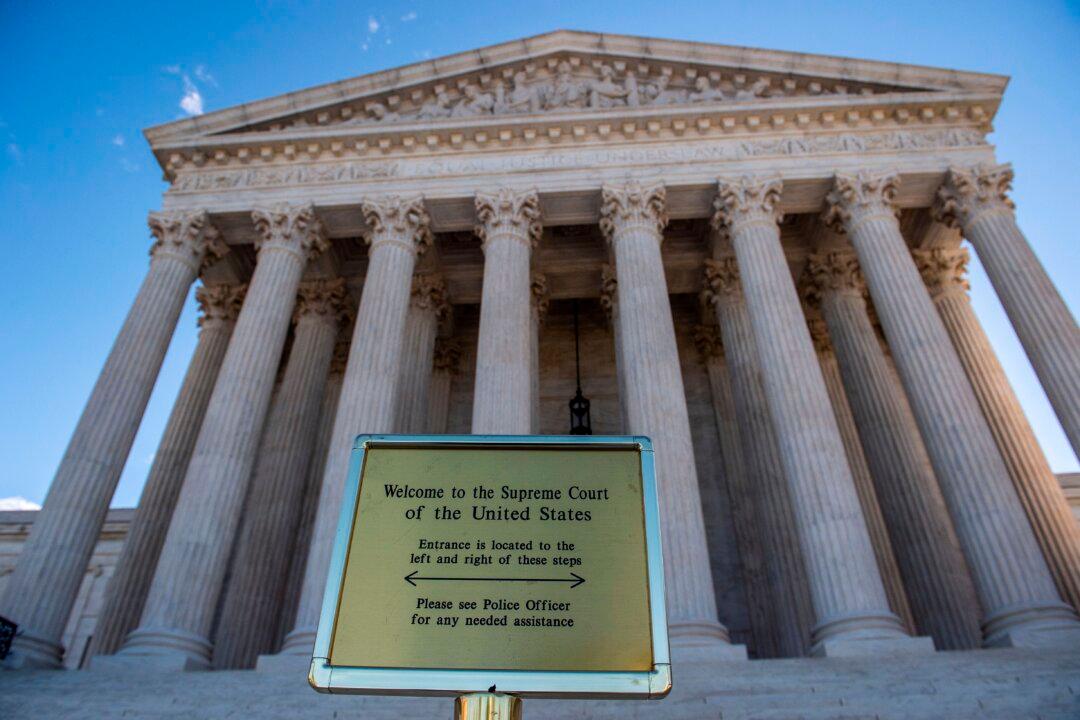

WASHINGTON—The Supreme Court overturned a ban preventing “immoral” or “scandalous” words and symbols from being trademarked, ruling the prohibition in the Lanham Act violated First Amendment speech protections.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which administers the intellectual property statute also known as the Trademark Act of 1946, previously rejected a trademark application for the word “F**T” (letters omitted) by clothes-maker and artist Erik Brunetti, who has said F**T stands for “Friends U Can’t Trust.” The designs include shirts, hoodies, and jackets.