WASHINGTON—Supreme Court justices split on ideological grounds on April 23 during high-stakes oral arguments about the legality of the Trump administration’s decision to ask individuals responding to the 2020 Census whether they are U.S. citizens.

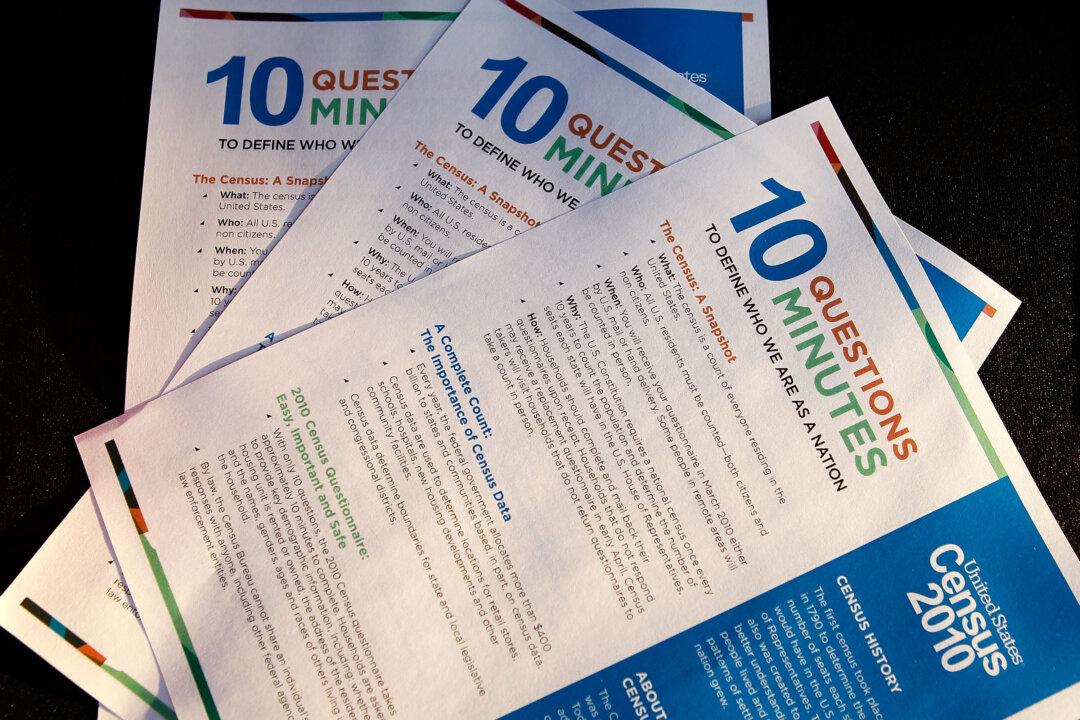

The results from the once-a-decade census, which counts both legal and illegal residents of the United States, are important because they are used to allocate federal dollars and determine representation in Congress.