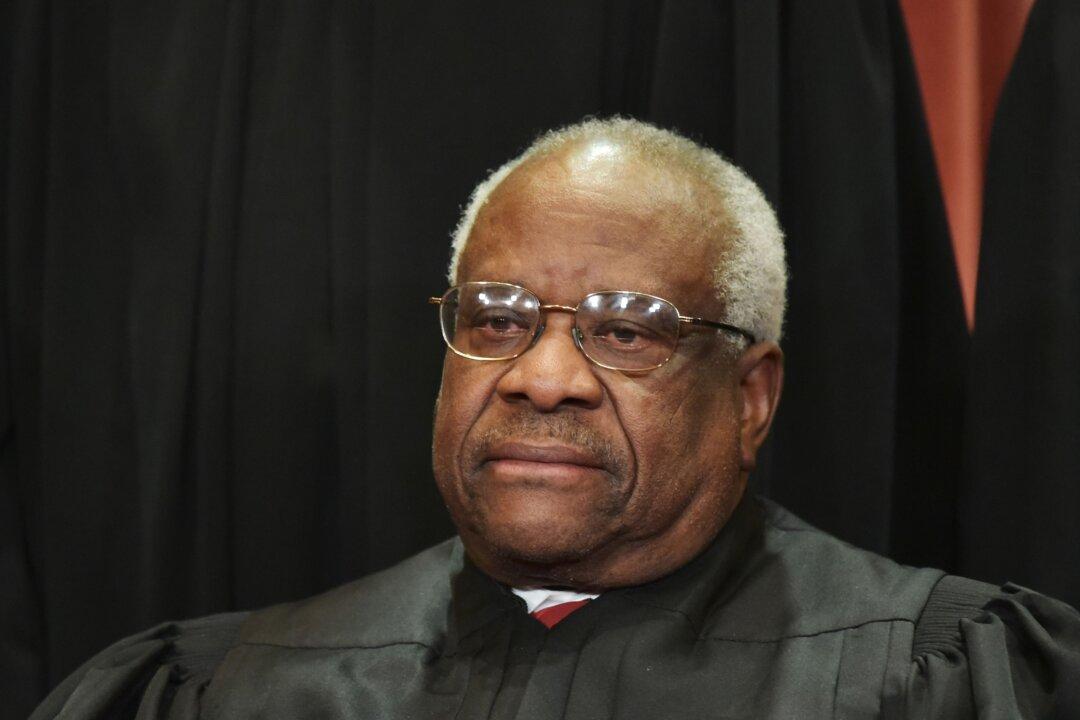

When Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas concurred in February 2019 in denying Katherine McKee’s request for a review of her status as a “limited public figure,” he included an observation that shook the mainstream news media.

McKee, who had claimed comedian Bill Cosby sexually assaulted her years ago, sued him for libel after Cosby’s lawyer publicly accused her of dishonesty.