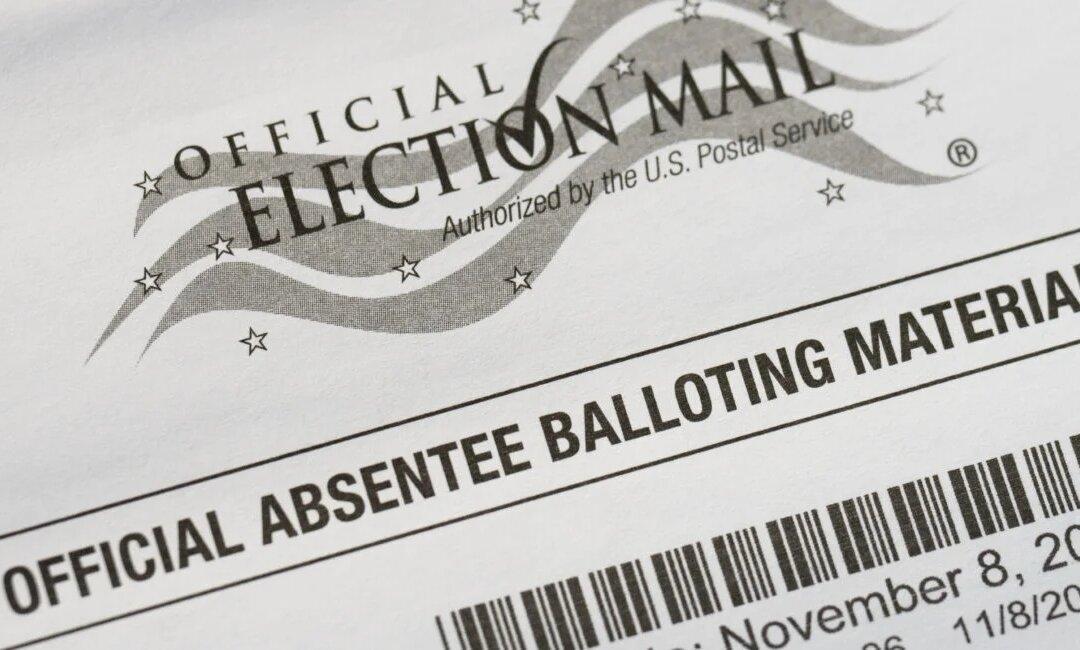

In a divided 2–1 opinion, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of a Tennessee law that bans the distribution of absentee ballot applications by nonelection officials. The ruling upholds a lower court’s decision, maintaining that the law does not infringe upon free speech rights.

The legislation, in place since 1979, had been challenged in 2020 by groups such as the Tennessee Chapter of the NAACP and the Memphis AFL-CIO on the grounds that it allegedly violated free speech rights protected by the First Amendment.