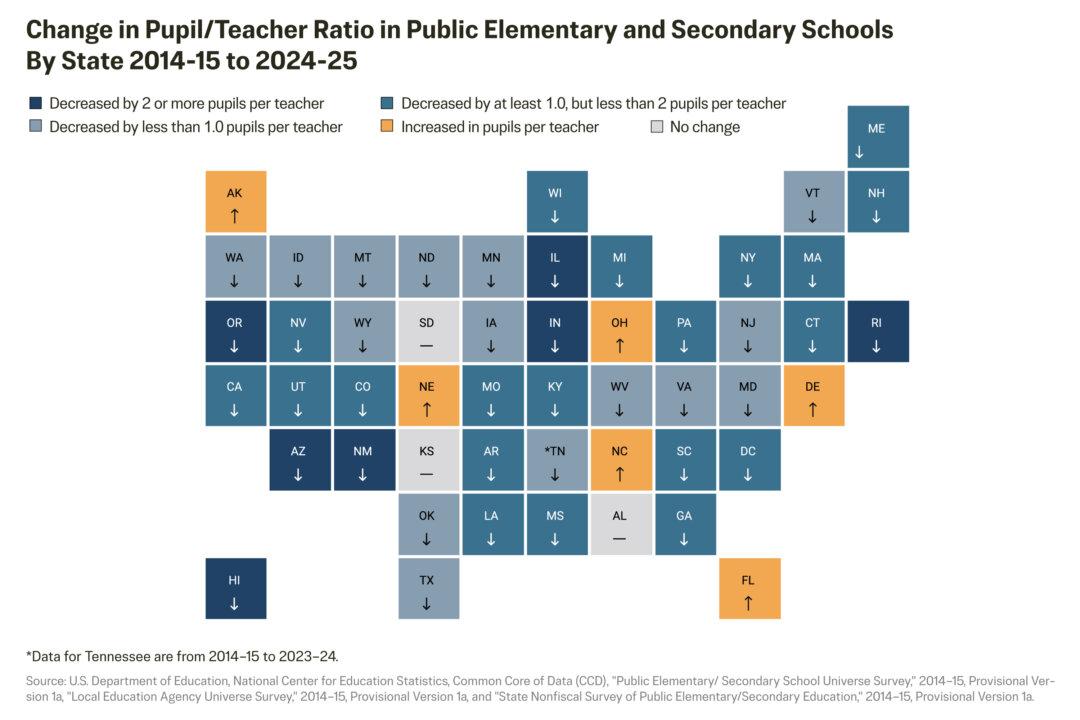

A financial crisis is looming in rural school districts across the country that many people have never heard of, local officials say.

Communities in 700-plus counties and 41 U.S. states with federally protected forest lands are exempt from property taxes, a primary revenue source for local school districts.