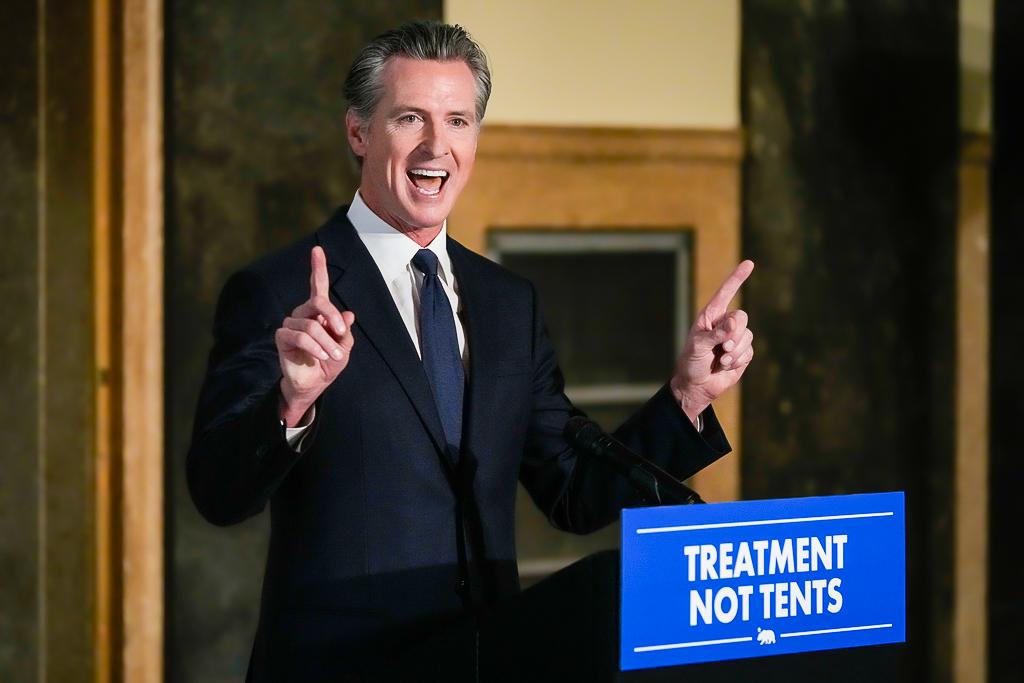

Propelled by $26 million in donations, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s Proposition 1 promises a long-overdue modernization of how California funds its mental health system. Voters will decide March 5 whether to approve the two-part measure, authorizing $6.4 billion in bonds and reallocating an existing wealth tax revenue for treatment beds and supportive housing.

Prop. 1 is the only statewide measure on the ballot, and by last week had amassed $16 million in donations. By March 1, another $10 million rolled in, according to the California Secretary of State’s website. Opponents of the measure have raised $1,000.