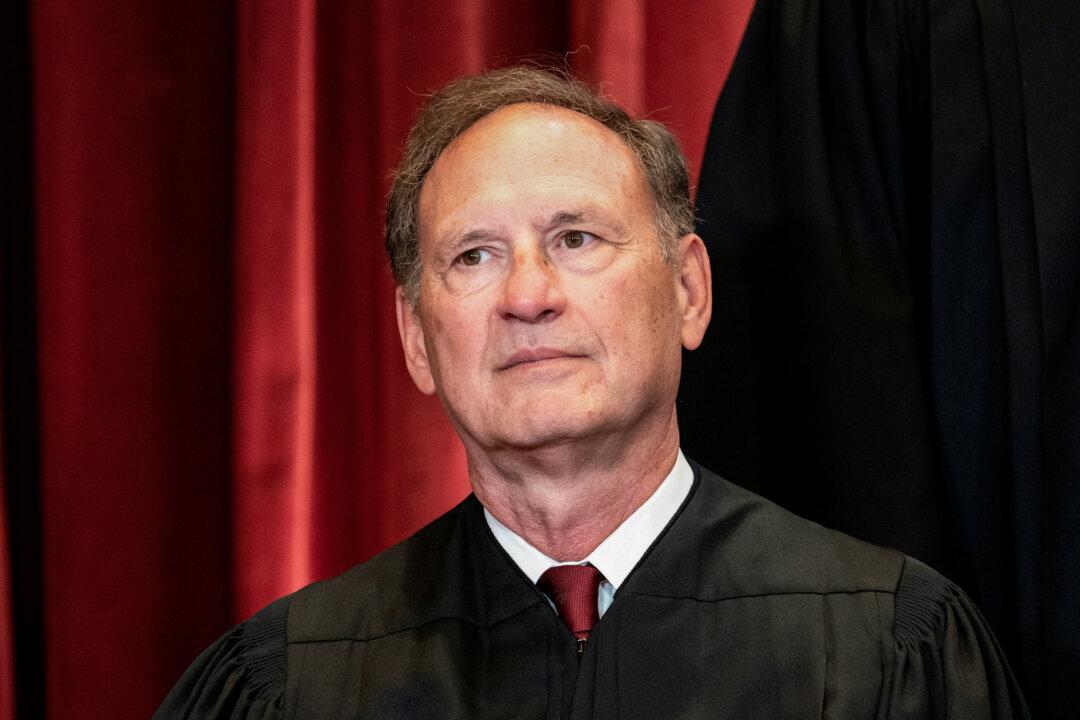

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito penned a strongly worded dissent deriding his colleagues’ May 16 decision to uphold a financial regulator’s controversial funding mechanism.

The case—Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) v. Community Financial Services Association of America (CFSA)—questioned the constitutionality of CFPB’s ability to determine its level of funding from The Federal Reserve, albeit with limited restrictions. The case is one of several posing major questions this term about the scope of administrative power.