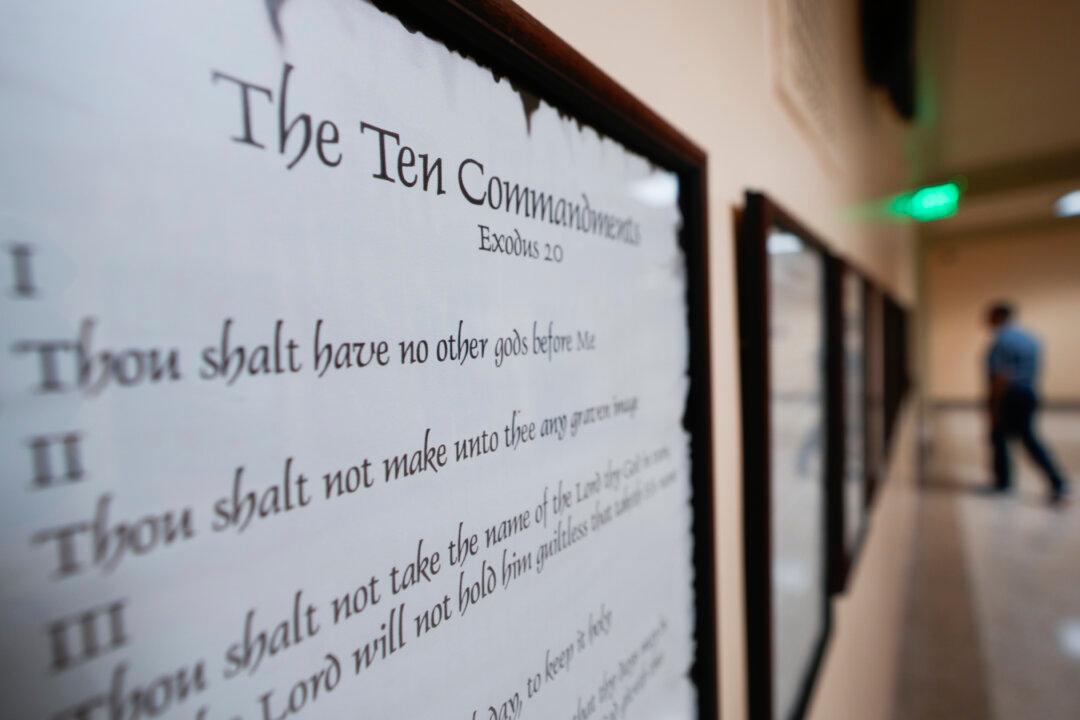

A federal judge approved on July 19 an agreement to pause a new law that requires Louisiana public schools to display the Ten Commandments after plaintiffs sued the state.

The parties’ counsels agreed that the defendants, which include state Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley, will refrain from posting the Ten Commandments “in any public school classroom before November 15, 2024.”