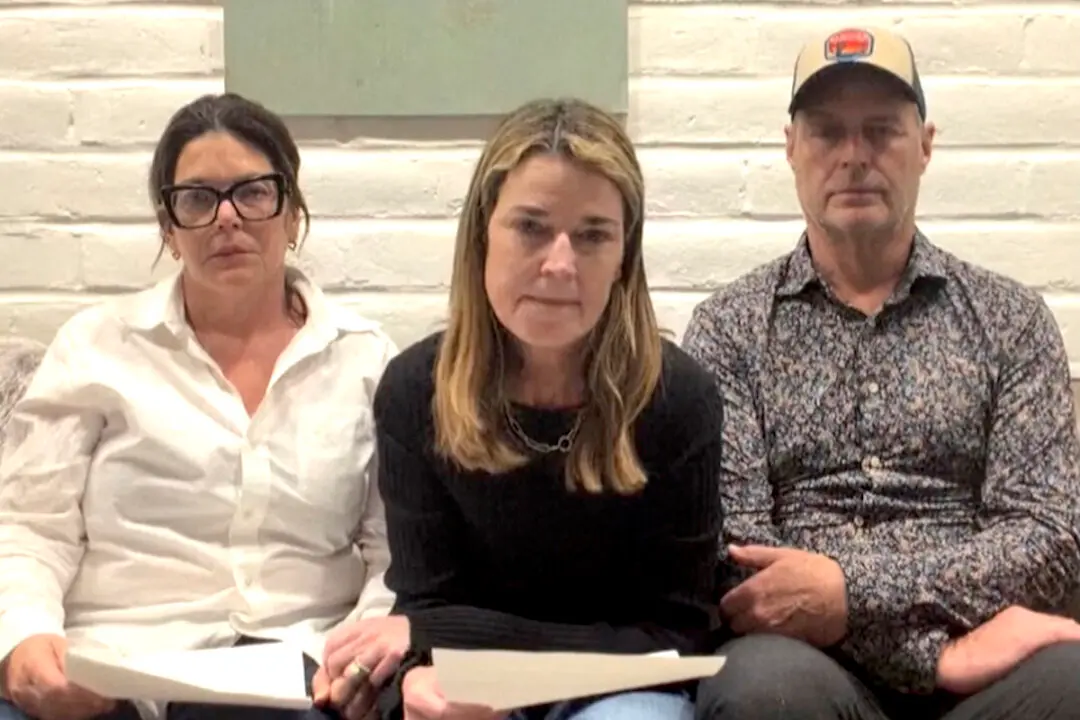

“I don’t want [Huntington Beach] to become another Santa Monica,” Gayline Clifford, a 37-year resident, said in response to the state’s demands for the Orange County coastal city to have more housing.

While the city faces pressure from the state to build more housing, including that which is affordable, some residents said they fear doing such might change its small-town “Surf City” vibe.