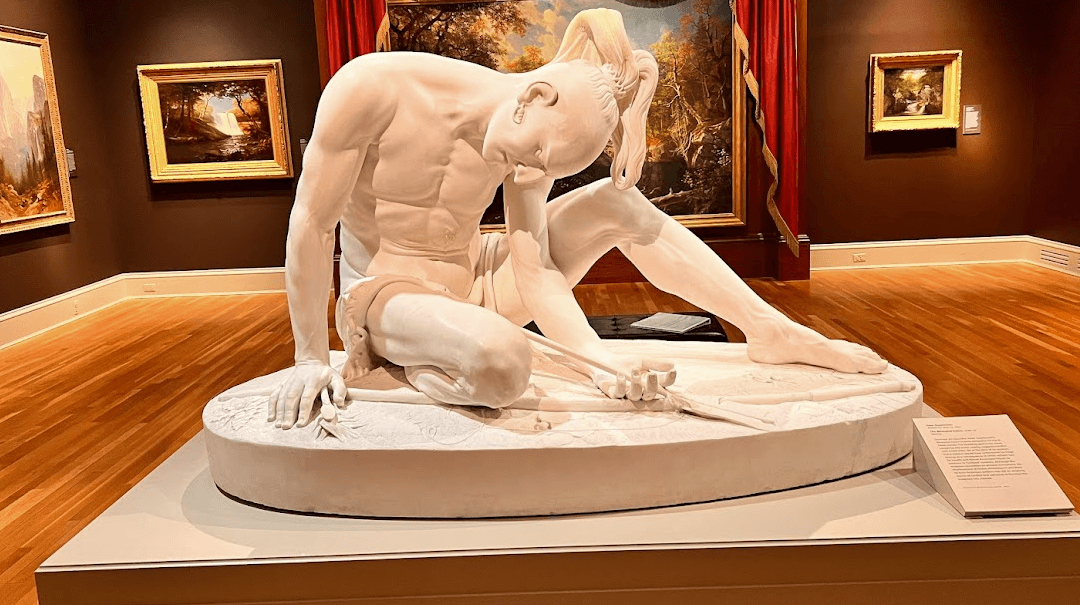

A story that seems more like a sequel to the popular movie “National Treasure” has ended with a stolen historic Boston statue presumed destroyed more than half a century ago instead being returned to the New England city after it was discovered on display some 600 miles away at an art museum in Virginia.

As it is readied for a return to Boston, the “Wounded Indian,” a beautiful statue carved out of white marble harvested from Vermont, brings together fabled American revolutionist Paul Revere, the FBI, a legendary American car maker, and an eccentric New York art collector who inspired an art forger, a poverty-stricken artist who went mad and died at a young age, along with a modern-day law firm as rare as the artifacts it has helped recover.