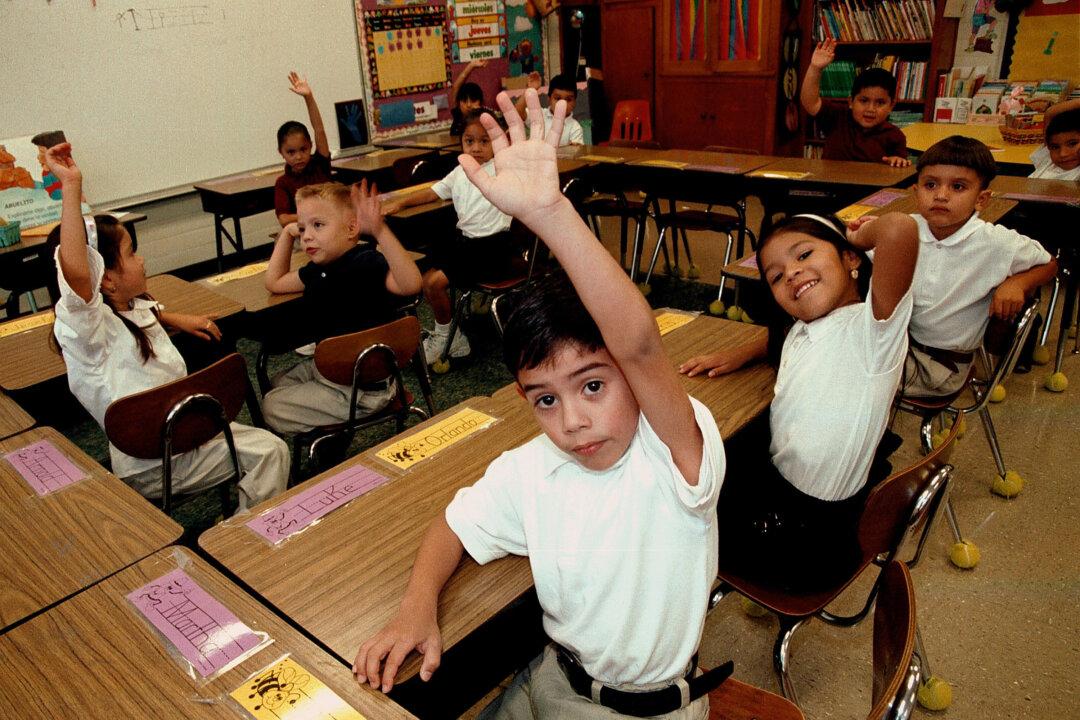

In his final days as U.S. secretary of education, Miguel Cardona provided every state governor with a plan he says will improve English language proficiency while still promoting the native languages that 5.3 million students speak at home.

His “Dual Language Immersion Playbook,” released on Dec. 19, asks public schools to consider providing instruction in two languages across multiple subjects, not just English or foreign language classes.