The Biden administration declined to send an official to a Dec. 7 congressional hearing on the closing of Guantanamo Bay, drawing anger from both sides of the political aisle over the apparent lack of attention the administration is giving to the issues surrounding the offshore detention center.

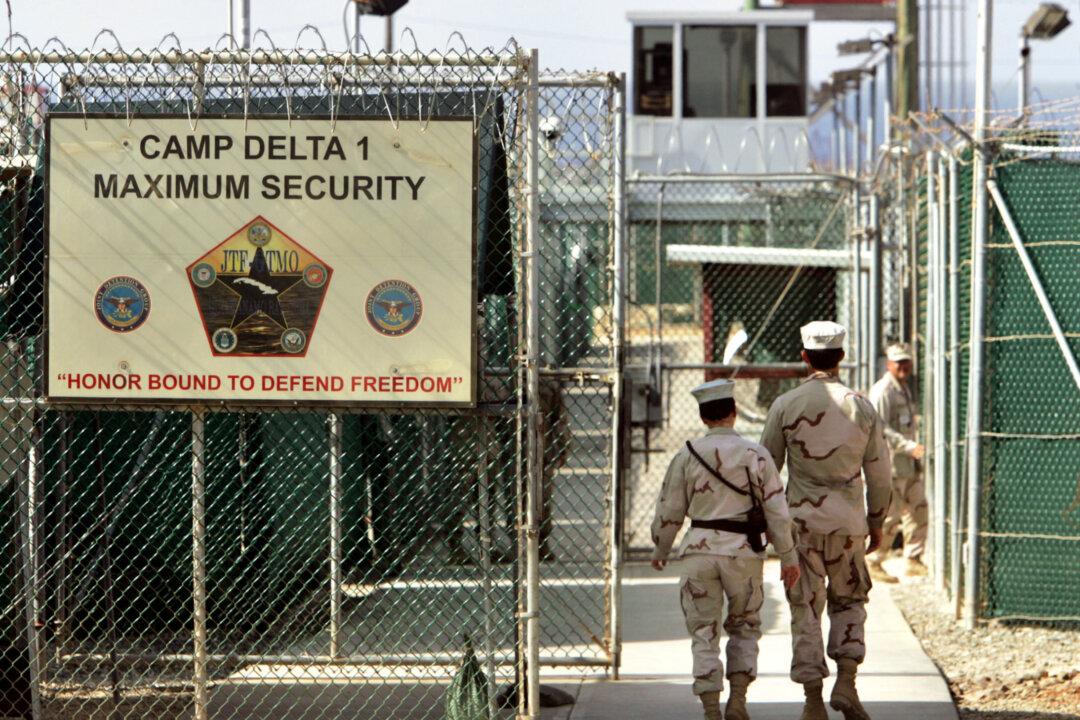

The Senate Judiciary Committee hearing is the latest in a series of efforts by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) to accelerate the process of closing the Guantanamo prison, which was opened in Cuba in 2002 following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Durbin co-wrote letters with Senate Democrats to Biden and Attorney General Merrick Garland in April and July, urging them to prioritize the matter. He also introduced legislation to close the facility last week.