Hong Kong cafes’ cultural history started earlier than in communist China, and the culture that developed did not originate from the mainland; the founder of the Museum of Hong Kong in the UK said at a two-day event (July 9-10) in London about Hong Kong’s traditional cafes.

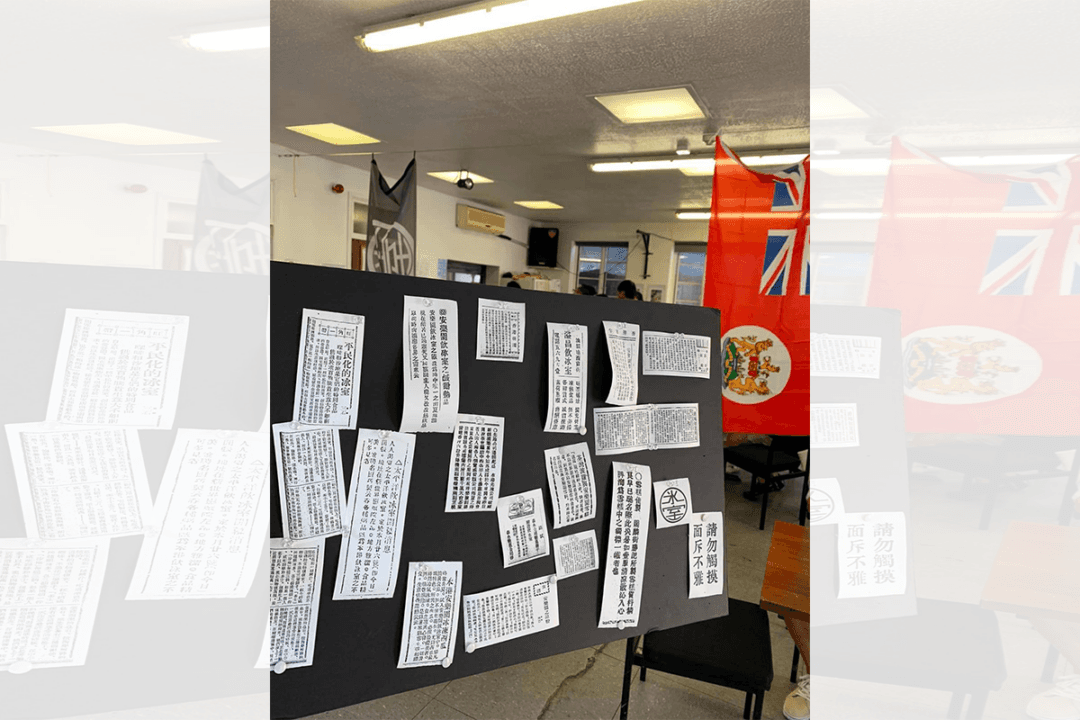

The event about Hong Kong’s bing-sutts (icehouse cafes) took place in London’s Hackney Chinese Community Services Centre, where the cafes’ unique flavours were reproduced for visitors.