News Analysis

In 2017, the No. 1 and No. 2 world economies will have a chance at a fresh political start.

A new team of executive officers handpicked by President-elect Donald Trump will join him when he becomes the 45th President of the United States in the White House in January.

Meanwhile, five out of seven members of China’s Politburo Standing Committee, the top decision-making body in the Chinese regime, are set to retire at an important political meeting slated for the second half of 2017. Also stepping down are at least two-fifths of the current Politburo and over half of the 376 elite Chinese officials in the Central Committee.

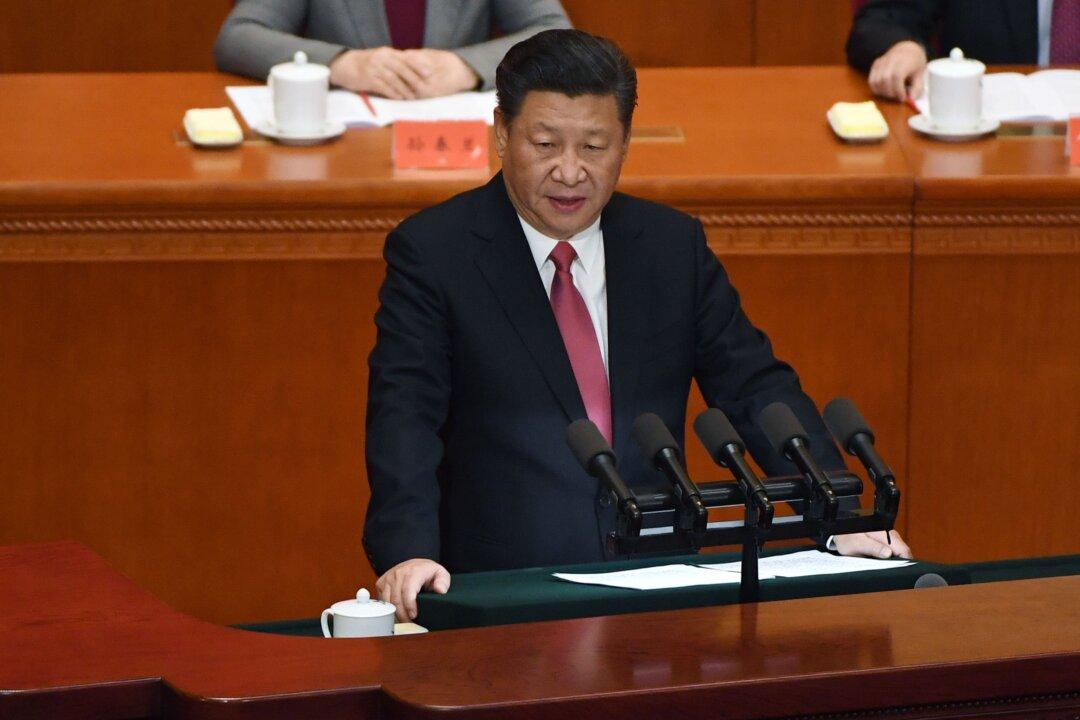

Chinese leader Xi Jinping will want to bring in loyal replacements to further entrench his anti-corruption campaign. He also appears committed to having the regime abide by its own laws, thus restraining corrupt officials.

But whether Xi will get his men into the top leadership group depends on the progress of consolidating his power over a rival political faction helmed by former Party chief Jiang Zemin.

Political Correctness

Jiang Zemin was Party general secretary from 1989 to 2002 and continued to oversee the Chinese regime for the next decade through the loyalists he placed in the administration of his successor, Hu Jintao.

Hong Kong and overseas Chinese media reported that Hu’s orders often wouldn’t leave the gates of Zhongnanhai, the official headquarters and residences of top Chinese leaders.

For instance, the military responded slowly to Hu’s instructions to provide emergency rescue in Sichuan when a massive earthquake struck in 2008 because the top generals still took directions from Jiang, as hinted by a retired general staff chief in his account of the rescue operations.

Jiang was able to secure a substantial following from both high- and low-ranking Chinese officials because he turned a blind eye to their corruption and kleptocracy. Ambitious officials also stood to gain if they took active part in Jiang’s initially unpopular persecution of a traditional Chinese spiritual practice.

“You must show your toughness in handling Falun Gong. … It will be your political capital,” Jiang had instructed his staunch loyalist Bo Xilai, according to veteran China journalist Jiang Weiping.

Bo oversaw the gang rape and abuse of female Falun Gong practitioners when he governed Liaoning Province in northeastern China. Liaoning was also the “epicenter” of harvesting Falun Gong organs, wrote American investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann in his 2015 book “The Slaughter.” When Bo later headed the southwestern metropolis Chongqing, the organs of an elderly practitioner were removed without his family’s consent and turned into medical specimens, the police claimed.

If Bo wasn’t investigated for corruption and prosecuted in 2013, he would likely be a Politburo Standing Committee member in Xi’s administration.