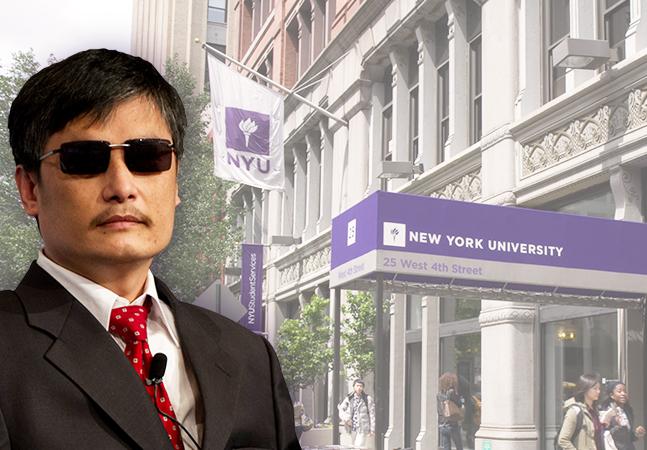

Chen Guangcheng, the blind Chinese lawyer whose dramatic escape from his highly surveilled hovel in the Shandong countryside led him to eventually be exiled from China, and take a position as a visiting fellow at New York University in May 2012, will be leaving the university within a month.

The news that NYU was ending its support for Chen was first reported by the New York Post in the early morning of June 13. “Chinese Takeout,” the headline read, in capital letters. “EXCLUSIVE: NYU boots blind dissident.” The New York Post did not speak to Chen before reporting the story.

According to a statement by the university, as well as a professor who works with Chen, and an individual close to him who did not wish to be identified, Chen Guangcheng and his wife knew they had to leave New York University at some point, and were not particularly surprised when asked to leave by the end of June.

Epoch Times contacted Chen and his wife, Yuan Weijing, multiple times on two cellphones via text message and voice calls, but after accepting a call, Yuan declined to provide the date that they were asked to leave NYU, or any other information; she said it was “inconvenient” to speak, and announced she would terminate the call.

Though they have been asked to vacate their apartment by the end of June, it is unlikely that they’ll be able to leave by that time, since on June 23 they are going to Taiwan for two weeks on a prearranged trip accompanied by Jerome A. Cohen, a professor of Chinese law at New York University who brokered their stay.

The university said in a statement that Chen was not put under any pressure regarding his public statements, but an individual close to him says they felt NYU did not wish Chen to be as vocal as he was about human rights in China, and that Chen felt somewhat pressured by the university. Chen also felt he was being pulled between conservative and liberal political interests in the United States, each wishing him to be exclusively associated with their causes as they related to human rights in China.

The Chens do not wish to comment on the reports until they have decided what they’re going to do next, according to the individual close to Chen. They currently have at least two offers to choose from: a three-year position at the Witherspoon Institute, a pro-life think tank in New Jersey, and a position as a visiting scholar at Fordham University’s law school, in New York.

The original report of Chen’s departure from NYU focused closely on the alleged pressure he had been put under by the university, and suggested that he was being forced to leave because the school was expanding in China, with a major campus in Shanghai.

The Post quoted an anonymous “New York-based professor familiar with Chen’s situation,” who said: “The big problem is that NYU is very compromised by the fact they are working very closely with the Chinese to establish a university. ... Otherwise, they would be much less constrained on issues like freedom of speech.”

In the statements by both professor Jerome Cohen and NYU spokesman John H. Beckman, this idea was explicitly discounted. “If it were true, why would NYU have taken Mr. Chen in at the height of the public fervor, and why would the Chinese authorities have given us permissions to move forward with our Shanghai campus AFTER his arrival here?” Beckman wrote. Cohen also said he had heard nothing about that.

The university had put Chen, his wife Yuan Weijing, and their two children, in an apartment near Washington Square Village in downtown Manhattan, where they took in the city and enjoyed “all the exotic foods the city has to offer,” according to an interview with Chen in the NYU Alumni magazine. Chen had a “custom-tailored” curriculum including constitutional law and the Declaration of Independence as his English study guide.

While he carried on his studies, Chen did become increasingly outspoken about human rights abuses in China, a turn of events that was perhaps not anticipated at the beginning of his stay at NYU.

An Associated Press story at the time said: “Some human rights advocates have said Chen can be more effective in the United States, where he can speak freely. But Cohen said Chen, who has received a fellowship to study at the university, will likely focus on his studies in the coming year and perhaps not devote as much time to his political activism.”

The piece then goes on to quote professor Cohen, who said, “Maybe he‘ll go back to China quickly at the end of the year, if things look good. Initially he’s going to put in a year of serious study and he’ll feel his way.”

Chen wanted to return to China “at some point,” the AP piece said.

That possibility became distinctly more remote over the following year, however.

Chen continued to make uncompromising statements about human rights in China, and the authorities continued to harass and punish his family members in China. Whether the increasingly tense relations between the Chinese regime and Chen Guangcheng and his family served to hasten Chen’s departure from NYU remains unclear.

His nephew, Chen Kegui, was sentenced to three years in prison in November 2012, supposedly for “intentional injury,” after he defended himself with kitchen knives from thugs associated with the local government, who broke into his house armed with clubs. “They had surrounded me, one man hit my head several times with a thick wooden club,” Chen said in an emotional interview after the encounter. “I had no choice but to slash with my knives.” Chen Kegui was also denied medical treatment for acute appendicitis, reports said, while other family members reportedly received death threats.

Chen’s elderly mother had her Social Security payments and telephone line cut off in May of this year.

Chen, meanwhile, continued to speak publicly about human rights abuses in China. He joined a coalition of 30 groups that had asked President Obama to raise the issue when he met with Party leader Xi Jinping in California last week and said “Communism has always been a scam” in a recent interview.

Most recently, Chen signed a letter with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu, which listed a litany of rights abuses in China. “Uncounted numbers of prisoners, credibly believed to be in the tens of thousands, have been executed and their organs harvested for sale—a practice so despicable it is nearly beyond our comprehension,” the June 4 letter said.