The food industry may be sitting on its next product goldmine—and most of us probably haven’t heard about it yet.

Microbiologists employed by the world’s largest food companies are still busy working on the research and development (R&D), so we can only guess what some of these new product creations will look like. What we do know is that there are going to be many, many.

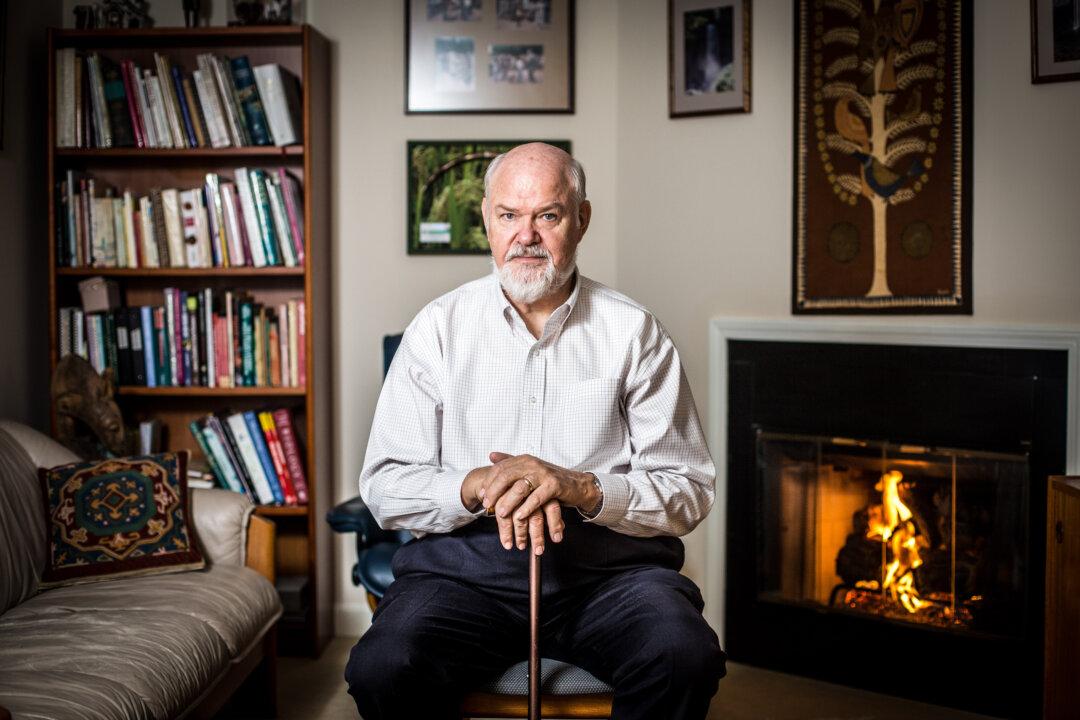

“In the coming years, you will be hard-pressed not to find miles and miles of food aisles with products that promote our microbiome,” said Jeff Leach, founder of the Human Food Project, and a pioneer in the rapidly advancing field of research involving the human microbiome.