Commentary

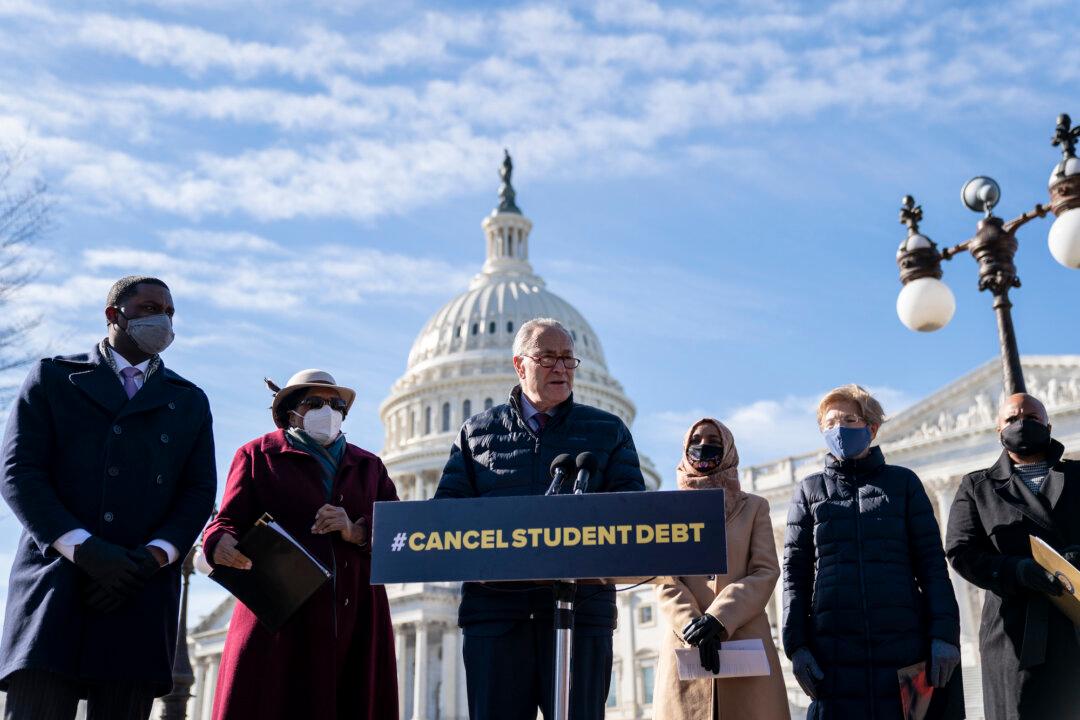

President Joe Biden’s approval ratings have sunk. Several Democratic strategists have suggested that they'll lift if the president fulfills his campaign promise to forgive student debt or at least a part of it.

President Joe Biden’s approval ratings have sunk. Several Democratic strategists have suggested that they'll lift if the president fulfills his campaign promise to forgive student debt or at least a part of it.