Commentary

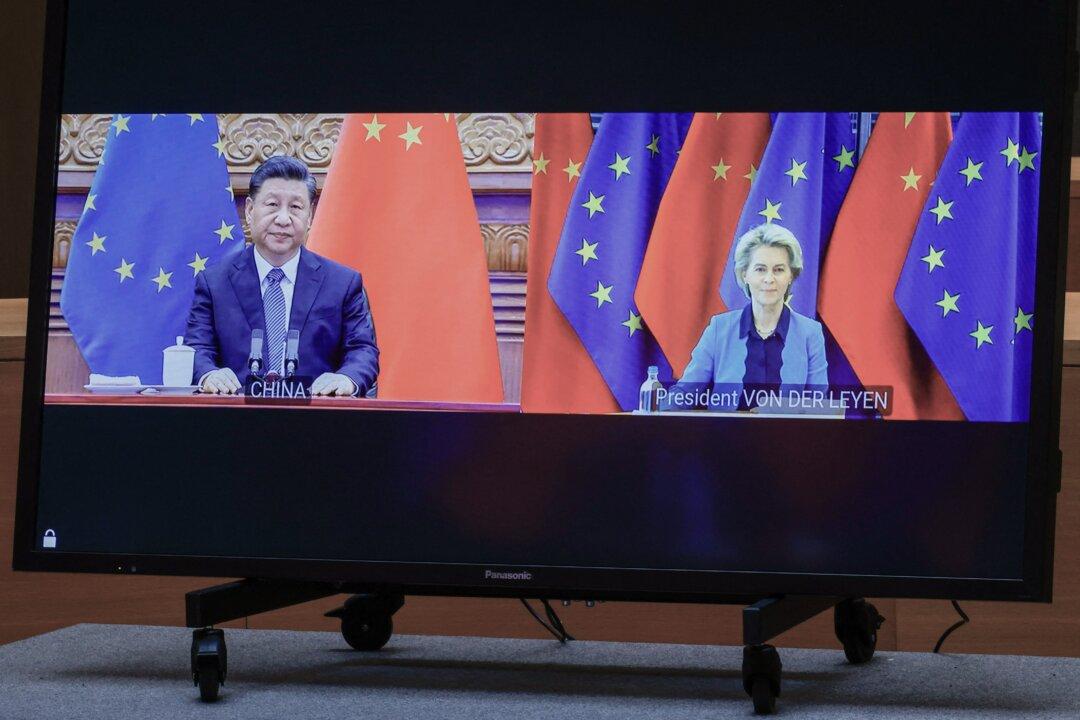

Mid-February marked the resumption of what used to be the biannual European Union-China human rights dialogue. The Munich security conference also took place on Feb. 17–19, with China playing a key role.

Mid-February marked the resumption of what used to be the biannual European Union-China human rights dialogue. The Munich security conference also took place on Feb. 17–19, with China playing a key role.