Analysis

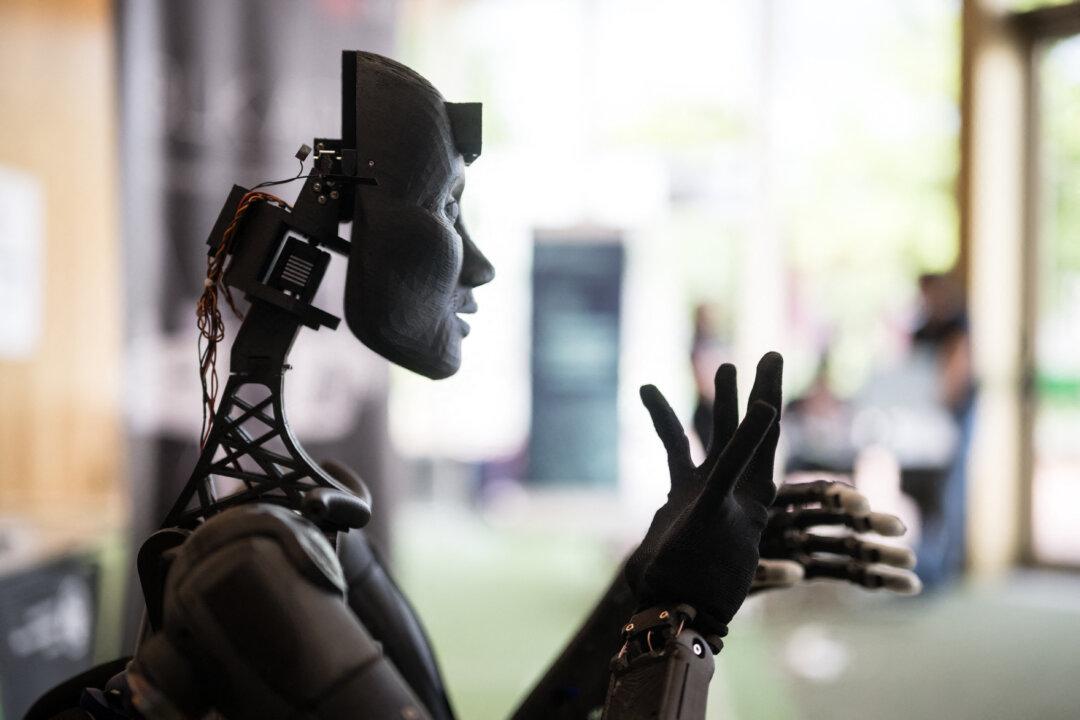

If the internet were the real world, it may very well resemble a sci-fi movie where robots have taken over the planet, or at the very least, started living alongside human beings.

If the internet were the real world, it may very well resemble a sci-fi movie where robots have taken over the planet, or at the very least, started living alongside human beings.