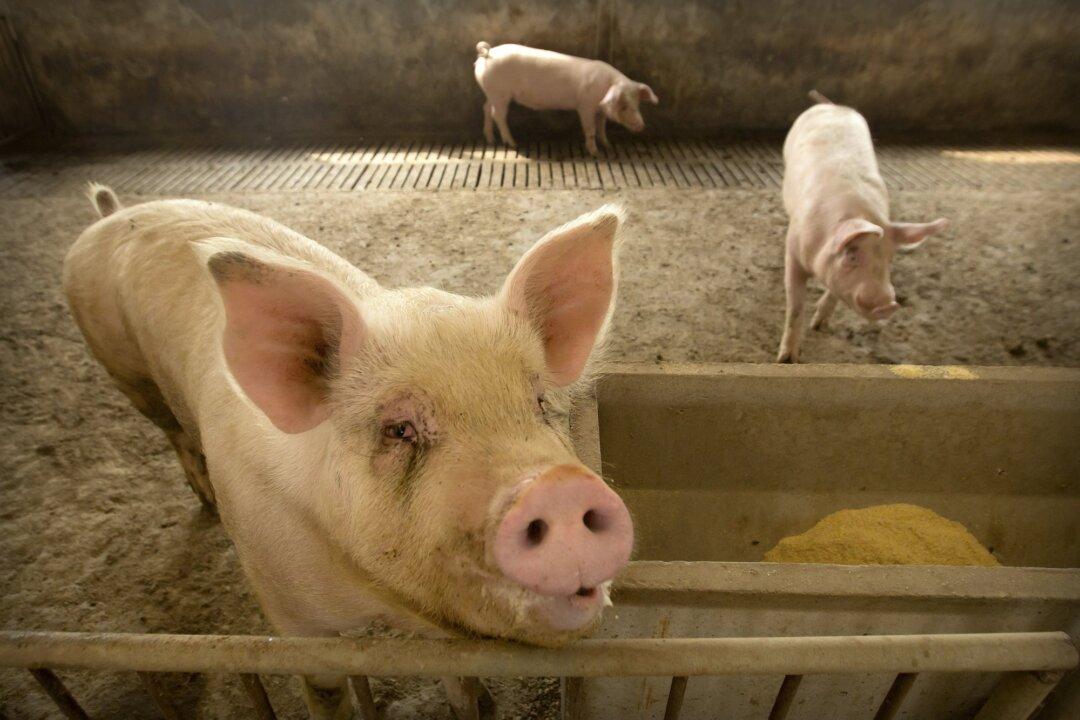

BEIJING—As many as half of China’s breeding pigs have either died from African swine fever or been slaughtered because of the spreading disease, twice as many as officially acknowledged, according to the estimates of four people who supply large farms.

While other estimates are more conservative, the plunge in the number of sows is poised to leave a large hole in the supply of the country’s favorite meat, pushing up food prices and devastating livelihoods in a rural economy that includes 40 million pig farmers.