BEIJING—Chinese universities sent students home and police fanned out in Beijing and Shanghai to prevent more protests Tuesday after crowds angered by severe anti-virus restrictions called for Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Xi Jinping to resign in the biggest show of public dissent in decades.

Authorities have eased some controls after demonstrations in at least eight mainland cities and Hong Kong—but maintained they would stick to a “zero-COVID” strategy that has confined millions of people to their homes for months at a time. Security forces have detained an unknown number of people and stepped up surveillance.

With police out in force, there was no word of protests Tuesday in Beijing, Shanghai, or other major mainland cities that saw crowds rally over the weekend. Those were the most widespread protests since the army crushed the 1989 student-led Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement.

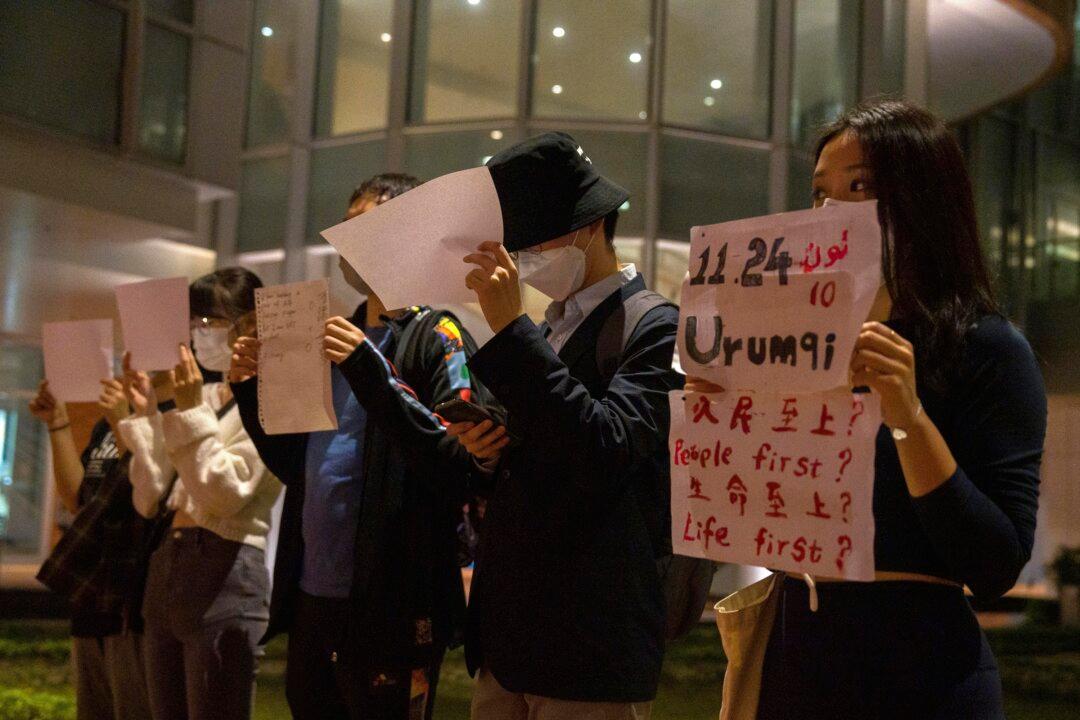

In Hong Kong, about a dozen people, mostly from the mainland, protested at a university.

Beijing’s Tsinghua University, where students rallied over the weekend, and other schools in the capital and the southern province of Guangdong sent students home. The schools said they were being protected from COVID-19, but dispersing them to far-flung hometowns also reduces the likelihood of more demonstrations. Chinese leaders are wary of universities, which have been hotbeds of activism including the Tiananmen protests.

On Sunday, Tsinghua students were told they could go home early for the semester. The school, which is Xi’s alma mater, arranged buses to take them to the train station or airport.

Nine student dorms at Tsinghua were closed Monday after some students positive for COVID-19, according to one who noted the closure would make it hard for crowds to gather. The student gave only his surname, Chen, for fear of retribution from authorities.

Beijing Forestry University also said it would arrange for students to return home. It said its faculty and students all tested negative for the virus.

Universities said classes and final exams would be conducted online.

Authorities hope to “defuse the situation” by clearing out campuses, said Dali Yang, an expert on Chinese politics at the University of Chicago.

Depending on how tough a position the CCP takes, groups might take turns protesting, he said.

Police appeared to be trying to keep their clampdown out of sight, possibly to avoid drawing attention to the scale of the protests or encouraging others. Videos and posts on Chinese social media about protests were deleted by the CCP’s vast online censorship apparatus.

There were no announcements about detentions, though reporters saw protesters taken away by police and social media posts said people were in custody or missing.

Police warned some detained protesters against demonstrating again.

In Shanghai, police stopped pedestrians and checked their phones Monday night, according to a witness, possibly looking for apps such as Twitter that are banned in China or images of protests. The witness, who insisted on anonymity for fear of arrest, said he was on his way to a protest but found no crowd there when he arrived.

Images viewed by The Associated Press of photos from a weekend protest showed police shoving people into cars. Some people were also swept up in police raids after demonstrations ended.

One person who lived near the site of a protest in Shanghai was detained Sunday and held until Tuesday morning, according to two friends who insisted on anonymity for fear of retribution from authorities.

In Beijing, police on Monday visited a resident who attended a protest the previous night, according to a friend who refused to be identified for fear of retaliation. He said the police questioned the resident and warned him not to go to more protests.

On Tuesday, protesters at the University of Hong Kong chanted against virus restrictions and held up sheets of paper with critical slogans. Some spectators joined in their chants.

The protesters held signs that read, “Say no to COVID panic“ and ”No dictatorship but democracy.”

One chanted: “We’re not foreign forces but your classmates.” Chinese authorities often try to discredit domestic critics by saying they work for foreign powers.

Global health experts have increasingly criticized the CCP’s “zero-COVID” policy as unsustainable.

Beijing needs to make its approach “very targeted” to reduce economic disruption, the head of the International Monetary Fund told The Associated Press in an interview Tuesday.

“We see the importance of moving away from massive lockdowns,” IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said in Berlin. “So that targeting allows to contain the spread of COVID without significant economic costs.”

Public tolerance of the onerous restrictions has eroded as some people confined at home said they struggled to get access to food and medicine.

The CCP promised last month to reduce disruptions, but a spike in infections has prompted cities to tighten controls.

The protests over the weekend were sparked by anger over the deaths of at least 10 people in a fire in China’s far west last week that prompted angry questions online about whether firefighters or victims trying to escape were blocked by anti-virus controls.

Most protesters over the weekend complained about excessive restrictions, but some turned their anger at Xi, the CCP’s most powerful leader since at least the 1980s.

In a video that was verified by The Associated Press, a crowd in Shanghai on Saturday chanted, “Xi Jinping! Step down! CCP! Step down!” Such direct criticism of Xi is unprecedented.

Sympathy protests were held overseas, and foreign governments have called on Beijing for restraint.

“We support the right of people everywhere to peacefully protest, to make known their views, their concerns, their frustrations,” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said during a visit to Bucharest, Romania.

Meanwhile, the British government summoned China’s ambassador as a protest over the arrest and beating of a BBC cameraman in Shanghai.

Media freedom “is something very, very much at the heart of the UK’s belief system,” said Foreign Secretary James Cleverly.

Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Zhao Lijian disputed the British version of events. Zhao said the journalist, Edward Lawrence, failed to identify himself and accused the BBC of twisting the story.

Asked about criticism of the suppression, Zhao defended Beijing’s anti-virus strategy.

Wang Dan, a former student leader of the 1989 demonstrations who lives in exile, said the protest “symbolizes the beginning of a new era in China ... in which Chinese civil society has decided not to be silent and to confront tyranny.”

But he warned at a news conference in Taipei, Taiwan, that authorities were likely to respond with “stronger force to violently suppress protesters.”