Dr. David Wyss believes the Fed is “hitting it as hard as they can,” but the half-speed economic recovery is not only due to the high debt levels and subprime housing that got the U.S. into a mess, but also due to Europe’s ongoing woes.

Dr. Wyss believes the Fed’s quantitative easing (QE) program served its purpose to unlock markets in 2009, but beyond that, it hasn’t been a big factor. The problem was one of the most synchronized world recessions in history being followed by a slow, less synchronized recovery.

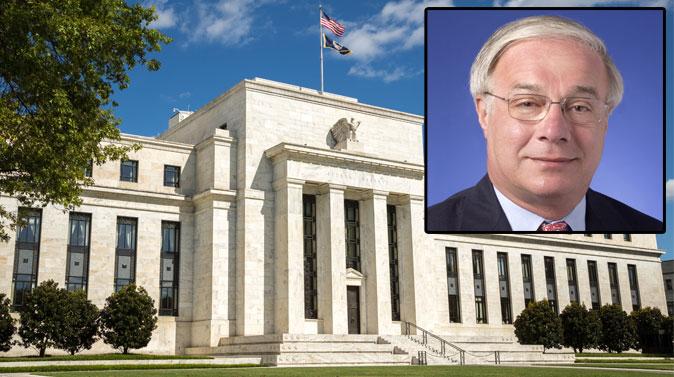

Dr. Wyss is Adjunct Professor at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. He was chief economist at Standard & Poor’s based in New York from 1999 to 2011. He has also held positions as senior staff economist with the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, senior economist at the Federal Reserve Board, and economic advisor to the Bank of England.

Dr. Wyss holds a Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University.

He spoke with Epoch Times on Oct. 17 about the slow U.S. economic recovery. He also touched on Canada’s housing market given what the U.S. has been through.

Epoch Times: The Federal Open Market Committee meets next week and is expected to end its latest QE program. How would you describe the Fed’s challenge now with the current market volatility and weakness in Europe and China?

Dr. David Wyss: The Fed has to determine what to do next and the economy still looks a bit iffy. You’ve got a lot of nervousness coming from Europe, in particular, and the slowdown in China. The Fed is thinking we can’t tighten as fast as we thought we could.

China’s economic growth is slowing down, but it’s still growing at a good rate. But I could be wrong. It could be worse than I expect.

Europe, I’m more worried about, and 40 percent of U.S. exports go to Europe. So, it’s potentially a significant hit to the U.S. economy. My feeling is it’s probably not enough to derail the recovery because we haven’t been getting growth out of exports anyway, but it’s going to keep things slow.

Problems in Europe and Japan will further cut developed country growth, with Europe likely to fall back into recession.

Epoch Times: In terms of evaluating QE, the unemployment rate target was reached quickly, but there has been talk of possible further QE. Has QE been successful? What cues does the Fed take from the volatility in markets as QE comes to an end?

Dr. Wyss: I think the initial QE1 was very important. The Fed had to do that. The second and third rounds of quantitative easing probably helped a little bit, but I don’t think they were a huge factor. What they’ve done is brought down long-term interest rates and mortgage rates.

But at the same time, it’s all the Fed has; the only tool they’ve got. They’re hitting it as hard as they can.

The Fed always pays attention to markets, particularly the bond market, and they should because a market tells you what people are expecting. But at the same time, I don’t expect quantitative easing to be revived, because I think the U.S. is doing OK.

When the U.S. starts raising rates, the dollar is going to strengthen, which is going to hurt exports, and we’re already seeing that.

But there are a lot of things that can go wrong. I’m more troubled by the European situation because I think while the Federal Reserve was behind the curve, the European Central Bank (ECB) didn’t even know there was a curve. And they’re in a mess—the Eurozone generally.

And they’ve been putting off dealing with the problem, the problem of excessive debt in Greece, the problem of uncompetitive economies in southern Europe because of inflation. And there’s not an easy way to fix this with standard policies.

Epoch Times: In terms of the labor market, with the U.S. unemployment rate falling to 5.9 percent, the labor force participation rate is at a 36-year low. It was falling pre-crisis and so it’s not just a phenomenon that has taken place post-crisis.

Dr. Wyss: The main reason for the labor force dropping is quite clear: The baby boomers are starting to retire. And when you hit retirement age you’re not in the labor force anymore. The average retirement age in the United States is about 62.

The baby boom started in 1945, so the people retiring today are people who were born in the early ‘50s during the peak of the baby boom. So they’re dropping out of the labor force.

The other big drop has actually been among younger people. They’re staying in school longer and I’m not sure that’s a bad thing either. I think that’s always a good thing, but part of it may be, “Well, I can’t find a job, so I'll stick with Mommy and Daddy for a little longer,” or stay in college.

But part of it, also, is people are discovering that without a college degree, it’s getting harder and harder to get a job. The unemployment rate for college grads is 2.9%, roughly half the national average. Suggests to me: I want a college degree.

Epoch Times: In the U.S., the ratio of home price to disposable income hit a peak in 2007 and Canada’s is at record levels now. Canadian borrowers’ indebtedness is similar to the U.S. situation prior to the subprime crisis. How do you see that problem being resolved unless a purging has to take place like it did in the U.S.?

Dr. Wyss: Frankly, my view is the Canadian housing market remains overvalued, but the economy has been pretty strong mainly because natural resource prices have been high. With oil prices now taking a dive, I think it’s going to make Canada a bit vulnerable.

The U.S. had a lot of things coming together to cause this crisis. Housing was just one of the factors. Housing was too affordable thanks to low mortgage rates. U.S. house prices rose about 75 percent from 1997 to 2005. Canadian house prices went up by almost 50 percent in that time period.

But now finally, starts and sales are recovering and prices have stabilized in the U.S. U.S. debt-to-income has dropped from its peak in 2007 of over 130 percent to below 110 percent.

In the U.S., the pool of underwater properties has halved since 2009. The share of homes with negative equity has come down from 26 percent in late 2009 to under 13 percent in early 2014. Foreclosures are at a six-year low.

Canada—especially as long as the U.S. remains relatively strong—doesn’t look like it’s going to hit quite as bad a blizzard. It’s not all going to happen at once like in the U.S., but I still think there’s going to be at best a period of stability of home prices, at worst a significant decline in Canada.

Epoch Times: In terms of the U.S. housing situation, with increased regulation that has been introduced since the crisis, is it more difficult for housing to boost the economy the way it used to given how low mortgage rates are? There was the famous case of Ben Bernanke not being able to refinance his mortgage. Is there a lesson there for the average American?

Dr. Wyss: There’s two reasons for not being able to refinance but reason No. 1 is you don’t have enough equity in the house, and that’s still a problem particularly in the hardest hit areas like Florida, Arizona, Nevada, and Detroit.

But in the rest of the country that’s easing, because home prices have come back up a bit. Another reason is bankers are getting a lot more serious about checking your income and checking how often you change jobs.

They are getting a little nastier on that and frankly, bankers are supposed to be nasty. I’m sure Bernanke managed to get his mortgage refinanced even though he got a rejection. But it’s a little harder.

You have to come up with more documentation. You have to do a better job of proving your ability and willingness to pay than you did, and frankly, that’s the way it should have been done back in 2006 and 2007.

Epoch Times: The savings rate in the U.S. is increasing and the U.S. consumer needs to spend in order for the economy to grow. So how does that get resolved?

Dr. Wyss: Slowly. The recession was caused by excessive debt. To get out of a recession, you spend money. If you’ve already got too much debt, you need to reduce your debt, which means you can’t spend. So it makes it hard to get out of these types of recessions and, of course, the recipe is for the government to do the spending.

But the government debt is getting pretty high and it ought to be, I feel. So what it means is things tend to be slow. Recoveries after high-debt recessions tend to be slower than other recoveries. Reinhart and Rogoff talked about this in their book [“This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly”].

Even though some parts were a bit discredited by the critics, but the basic argument holds up. High levels of debt mean slower recovery.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

MORE:

- Fed Keeps Rates Low As Economy Still Needs Time to Heal

- Bank of Canada Holds Policy Rate at 1% With Risks Balanced

*Image of “Federal Reserve“ via Shutterstock