The Trudeau government is taking on the four provinces that have resisted its federal carbon pricing plan by promising $2 billion in annual rebates to offset the costs. But the federal Conservatives and the four premiers against the tax have called the move an election ploy and a tax grab, and vow to keep fighting.

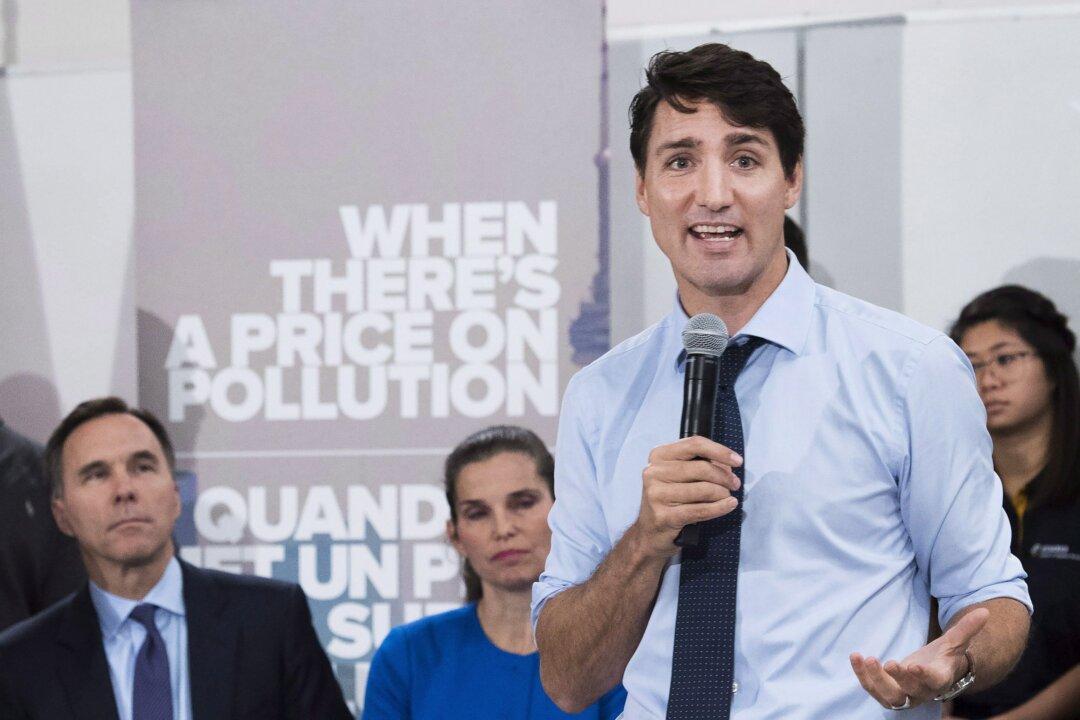

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said it will no longer be free to pollute in Canada and a tax on carbon emissions is the best way to combat climate change. He made the announcement on Oct. 22 in the riding of carbon tax foe Ontario Premier Doug Ford in north Toronto.