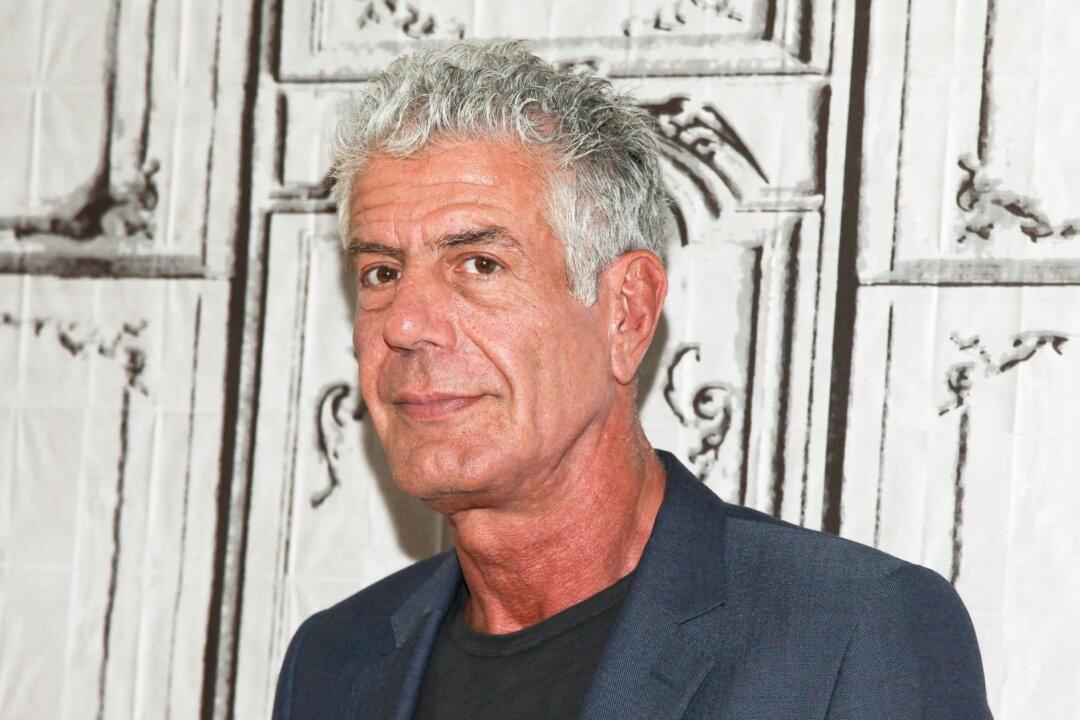

Alexandra Robbins is an overachiever. She graduated summa cum laude—the highest distinction—from Yale only to realize on the very day of graduation that it didn’t mean anything to her.

Being a typical overachiever, she had equated her self-worth to her goal to such an extent that it had taken precedence over everything else. Her pursuit of success did not lead to happiness, an understanding she details in her book “The Overachievers: The Secret Lives of Driven Kids.”