Commentary

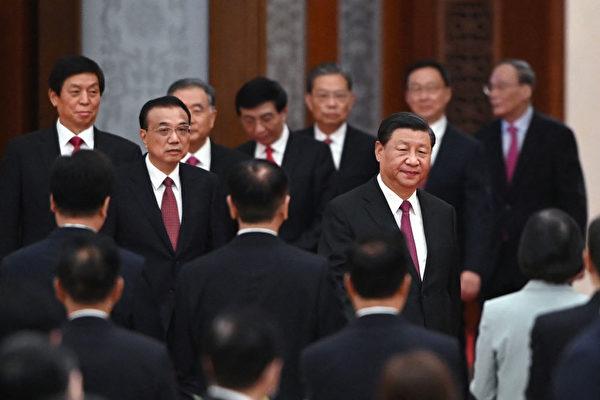

Xi Jinping will present a historic resolution at this week’s sixth plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 19th Central Committee.

Xi Jinping will present a historic resolution at this week’s sixth plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 19th Central Committee.