Commentary

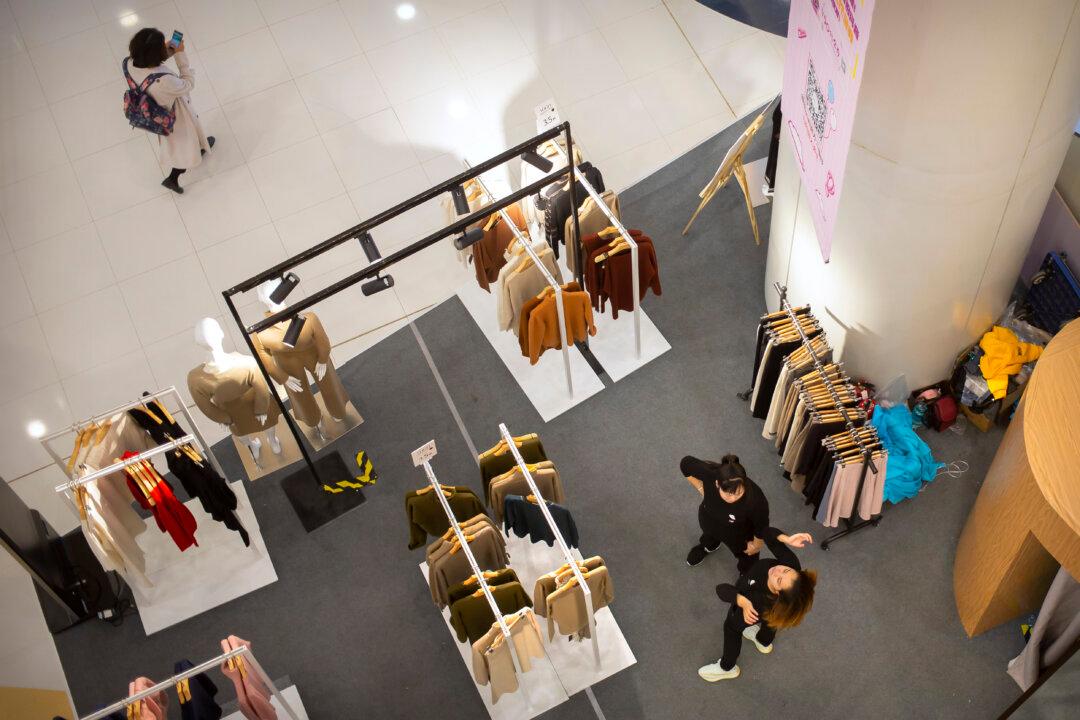

While the property crisis takes pride of place as China’s biggest economic problem, the uneasy state of Chinese consumers is more fundamental and perhaps more telling.

While the property crisis takes pride of place as China’s biggest economic problem, the uneasy state of Chinese consumers is more fundamental and perhaps more telling.